A review of primary healthcare practitioners’ views about nutrition: implications for medical education

Clare Carter, Joanna E. Harnett, Ines Krass and Ingrid C. Gelissen

School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, New South Wales 2006 Australia

Submitted: 02/11/2021; Accepted: 03/05/2022; Published: 26/05/2022

Int J Med Educ. 2022; 13:124-137; doi: 10.5116/ijme.6271.3aa2

© 2022 Clare Carter et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use of work provided the original work is properly cited. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0

Abstract

Objectives: This study aimed to review literature that reports on the perspectives and opinions of Australian and New Zealand primary healthcare practitioners on their role in nutrition counselling of their patients.

Methods: A systematic search of relevant articles reporting on attitudes towards nutrition counselling by Australian and New Zealand doctors/physicians, nurses including midwives, pharmacists and dentists was conducted. The search included literature from the past ten years until March 2021 and identified 21 relevant papers, with most of the studies including medical practitioners and nurses.

Results: Three main themes were identified from qualitative and quantitative data, which included education and training, practitioner experiences and challenges. Consistent with previous literature, health care practitioners acknowledged their important role in the provision of dietary advice to patients. Challenges that influenced the provision of this advice included insufficient education and training, time constraints and limited knowledge and confidence. Time constraints during normal consultations led to a low priority of nutrition counselling. An absence of assessment opportunities to demonstrate nutrition competence and limited coverage of specific nutrition-related advice during training were also reported.

Conclusions: Primary healthcare practitioners acknowledge the importance of playing a role in the provision of nutrition advice but require education and access to evidence-based information that can be utilised effectively within the time constraints of standard consultations. Medical education curricula can be improved to provide more emphasis on nutrition education, including relevant assessment opportunities.

Introduction

The World Health Organisation (WHO) describes nutrition as a ‘fundamental pillar of human life, health and development across the entire life span’.1 The rise in poor dietary habits, underpinned by the consumption of energy-dense foods high in saturated and trans-fats, refined sugars, and excess salt, has precipitated a worldwide epidemic of non-communicable diseases.2 Nutrition is a key modifiable determinant of non-communicable diseases, for which evidence illustrates the impact of changing dietary patterns on health outcomes.2 More specifically, dietary interventions play a crucial role in the prevention and treatment strategy of chronic diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease and hypertension.2 In 2017, dietary risk factors accounted for 11 million deaths globally.3

In addition to the valuable role of dieticians, who are instrumental in the education of patients with existing chronic diseases, it has been recognised worldwide that primary healthcare practitioners can also play a fundamental role in the provision of evidence-based nutrition information to patients.4 For the purpose of this study, the term ‘primary healthcare practitioners’ describes medical doctors/physicians, pharmacists, nurses and/or dentists. Primary healthcare practitioners are regarded as a relatively large, affordable, and accessible community for whom the implementation of strategies to guide the provision of nutrition care could be advantageous. This is apparent in rural settings where access to dieticians may be limited.5,6 An understanding about the knowledge, skills and attitudes of primary healthcare practitioners towards their role in the promotion of healthy nutrition is warranted.

While several studies have reported healthcare practitioners’ perceptions about dietary counselling, a comprehensive review of literature including primary healthcare practitioners of Australia and New Zealand has previously not been conducted.7, 8 Therefore, the aim of this review was to identify and summarise the current literature that documents primary healthcare practitioners’ self-perceived knowledge and opinions about the role and readiness to counsel patients on healthy nutrition. The findings of this review will inform the development of education initiatives that aim to equip primary healthcare practitioners with the knowledge and skills required to provide dietary counselling to their patients.

Methods

A systematic search and review, as described by Grant and Booth was conducted to identify and summarise peer-reviewed literature that reported perspectives of Australian and New Zealand primary healthcare practitioners about their knowledge and readiness to counsel patients in nutrition.9 Australia and New Zealand were chosen due to socio-demographic similarities of the populations and similarities in the training of primary health care practitioners.

Search Strategy

Medline, Embase, Web of Science and Scopus were searched for key concepts related to nutrition and primary healthcare practitioners’ provision of dietary counselling. Google Scholar was also searched to capture any articles not identified in the main search. The search was conducted between 19th March and 9th April 2021. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were agreed upon by three authors, and a University of Sydney Faculty of Medicine and Health librarian was consulted regarding the search strategy. The following studies were included: original research studies conducted in Australia and New Zealand adults, written in English, reporting on primary healthcare practitioners’ opinions about dietary counselling, involving doctors/physicians, nurses (including midwives), pharmacists and dentists. Only articles from the past ten years were included to align as much as possible with the most recent curricula provided to health care practitioners. Studies were excluded if they involved allied healthcare professionals, including dieticians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, chiropractors, naturopaths and complementary medicine practitioners (e.g., herbalists) and complementary medicine products. In addition, any studies involving participants who were students were also excluded. Furthermore, review articles, books, policy documents and conference proceedings were excluded, as were articles in languages other than English or those involving countries other than Australia and New Zealand. Search results were uploaded into EndNote, and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened by one author (C.C.) and checked by two additional authors (I.G. and J.H.). Full-text articles included in the study were screened by three authors (C.C., I.G. and J.H.) to confirm eligibility and extraction of relevant data as outlined below. A PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search methodology is included in Appendix 1.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted, summarised, and tabulated using author, year of publication, aims, study method, sample population and sampling methods, as well as key findings and outcomes (Table 1). As the survey tools utilised in the studies varied substantially, including qualitative data generated from interviews and focus groups, further analysis was performed to assist in the interpretation and organisation of data, utilising the six phases of analysis by Braun and Clarke.10 This included initial data familiarisation and key concept identification by one author (C.C.), followed by coding and identification of meta themes and sub-themes agreed upon by three authors (C.C., I.G. and J.H.). Discussions throughout the analysis process allowed for consensus between members of the research team regarding the interpretation of data, theme conceptualisation and naming.

Results

A total of 520 articles were identified in the literature search, with an additional article retrieved through Google Scholar. Following the title and abstract screening of 382 articles, 30 articles were assessed for suitability against our inclusion criteria and critically evaluated, with a total of 21 articles included in the systematic review.

An overview of the studies is presented in Table 1, including the aim, the population studied, the methods utilised, and the major findings reported by the authors. With regards to the primary healthcare practitioners sampled in the articles, the following breakdown of healthcare practitioners was found: general practitioners (n=10), general practitioner registrars (n=3), general practitioner interns (n=1), general nurses (n=10), midwives (n=2) and pharmacists (n=1). Participant numbers averaged 125 (range 9 – 393), with 9 out of 21 studies having >100 participants. Study methods included quantitative methods (questionnaires and surveys; n=16 with a mix of paper and online delivery), qualitative methods (semi-structured interviews n=4; focus groups; n=1) and mixed methods (n=1). The predominant sampling method was convenience sampling. The topics covered included general nutrition (n=7), pregnancy (n=5), nutrition and chronic conditions (including type II diabetes; n=4), nutrition and cancer (n=2), and more specialist branches of nutrition (enteral nutrition, malnutrition and dehydration, and nutrition for patients with brain injuries; n=3).

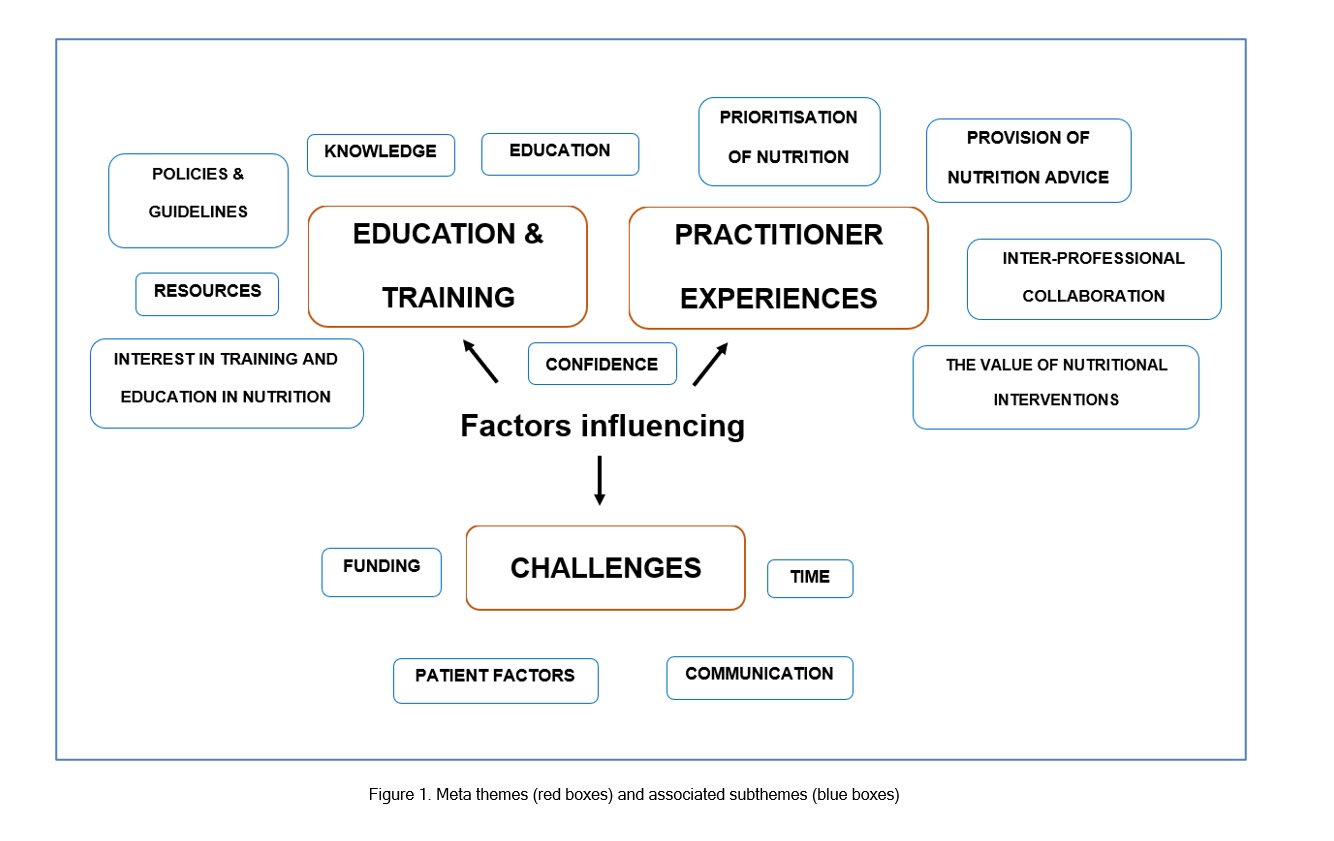

After coding of articles, three meta themes and fourteen subthemes were identified from the qualitative data as well as the topics and outcomes from the quantitative surveys and questionnaire data. Figure 1 illustrates the meta themes, which were 1) education and training, 2) practitioner experiences and 3) challenges, presented in red, with associated sub-themes in blue. Table 2 provides an overview of selected quotes, supporting the meta themes and sub-themes. The quotes were extracted from individual references and reflected the perspectives of the study participants.

Discussion

This review provides a comprehensive overview of primary healthcare practitioners’ perspectives about the counselling of patients in nutrition in Australia and New Zealand. The results illuminate several key factors that influence the opinions of primary healthcare practitioners regarding the provision of nutrition advice to patients. Firstly, primary healthcare practitioners clearly perceive the provision of nutrition advice as their responsibility, with only one article including general practitioners reporting that the provision of detailed nutrition counselling was not considered part of their role.7 This is consistent with previous literature, suggesting that healthcare professionals should conduct a nutritional assessment, provide basic evidence-based nutrition advice, and refer patients to a dietician when necessary.4,30-32 As healthcare practitioners are accessible to a large proportion of the population, this provides opportunities to discuss nutrition, encourage dietary changes and support the long-term maintenance of these dietary changes.8,22 However, uncertainty regarding an operational definition of basic nutrition care was reported by some primary healthcare practitioners, who found it difficult to differentiate their professional roles.8,13,18 Clarification of the scope of practice of healthcare practitioners in relation to nutrition may relieve uncertainty and enhance confidence in the delivery of such information.21 Professional associations could consider the development of a position statement or guiding principles to achieve this outcome.

Secondly, a recurrent sub-theme across the studies reviewed was the perceived value and impact of primary healthcare practitioners on patient health outcomes.18,22,26 Perspectives were positive about the impact of dietary counselling on changing patients’ eating patterns, where healthcare practitioners strongly agreed that nutrition is a key determinant of health outcomes.18,22,26,27 This concurs with the view of the WHO that the provision of nutrition services is associated with improved maternal, infant, and child health, a lower risk of chronic disease and improved life expectancy.33 Recognition of the crucial role of dietary interventions in the prevention and treatment of non-communicable diseases can influence the frequency of dietary counselling by primary healthcare practitioners.8 However, while nurses reported that they believed there is considerable evidence to support the success of dietary interventions, the strength or extent of this evidence was unknown to them.26 The lack of awareness of primary healthcare practitioners, prompted by a deficiency in nutrition knowledge, can precipitate negative beliefs about the effectiveness of nutrition interventions.13 Health professionals, particularly doctors, are shown to influence patients’ nutrient intake; hence there is a need for healthcare practitioners to lead and promote a collaborative nutrition care approach.34 This may be achieved by ensuring all healthcare practitioners adopt the view that improving their patients’ nutritional habits will improve patient outcomes.34 Additionally, the development of objective outcome measures to quantify the benefits of nutrition therapy may modify practitioners’ perspectives and help in this matter.13

Despite the importance of nutrition and its role in the provision of advice to patients, primary healthcare practitioners were often not able to translate this priority into practice due to a lack of education and training, with a clear gap in knowledge identified across several areas of nutrition.8,13,15,35 This may lead to the provision by practitioners of nutrition education based on personal experiences and perspectives rather than evidence-based guidelines, which can be of concern.13,35 It was also apparent that primary healthcare practitioners’ knowledge deficits impede their confidence in the delivery of nutrition information to patients.25,28,29 Lack of evidence-based nutrition knowledge and associated confidence is underpinned by inadequate nutrition education during and after their formal training.15,17,23,24 This lack of confidence was also noted in a study from Germany, where less than half of general practitioners surveyed believed that they had successfully changed the dietary habits of their patients.36 Specifically, studies included in this review emphasised an absence of assessment opportunities to demonstrate nutrition competence and limited coverage of specific nutrition-related advice during training.12,15 Following registration, there is often limited availability and accessibility of nutrition education opportunities and resources. It is therefore unsurprising, that another strong theme identified in this review was primary healthcare practitioners’ interest in receiving additional education and training in nutrition.8,20,21,29 This concurs with the findings of previous studies that identified insufficient education in nutrition, including a lack of nutrition assessment skills that translate into clinical practice.30,35,37 Implementation of a comprehensive nutrition curricula into existing Australian and New Zealand curricula and an increase in available educational opportunities and resources is clearly warranted. In Australia, a Nutrition Competency Framework was developed in 2016 to guide the inclusion of several knowledge and skills-based nutrition competencies in Australian medical curricula. This Framework has, however, to our knowledge, not been formally adopted by the Australian Medical Council, which regulates the Australian and New Zealand medical education. In New Zealand, a nutrition syllabus was introduced in 2012 in general practitioners' training. However, the effectiveness of this syllabus remains to be assessed.38,39 A recent comparative analysis of nutrition incorporated into medical curricula worldwide showed that only 44% of the Australia and New Zealand accreditation documents included in the study had requirements for nutrition education.40 A systematic review of worldwide literature on the provision of nutrition education to medical students also identified a lack of consensus in education worldwide and concluded that medical students are not provided with adequate nutrition training, calling for institutional commitment to improve nutrition education.41 Clearly, there is scope to improve nutrition education of medical practitioners worldwide, including assessment opportunities.

The capacity of primary healthcare practitioners to guide and provide evidence-based information to patients is further impacted by additional challenges, including time constraints, funding and prioritisation of nutrition. In Australia and New Zealand, primary health practitioners consistently reported that the time length of patient consultations highly influenced their decision to counsel patients on nutrition.7,8,25-27,35 For example, practitioner nurses and general practitioners indicated that 5-10 minutes and 1-5 minutes respectively were spent on discussions on patients’ diet and the provision of nutrition advice.22 Literature has stressed that building rapport and getting an understanding of the psycho-social requirements of patients is needed to motivate dietary changes of patients – a process that takes significantly longer than a typical 15-minute healthcare practitioner appointment.37 Time constraints are clearly a major challenge to the provision of nutrition advice; however, this is not a challenge that can be easily addressed as it would require budgets allocated to the provision of healthcare to include funding time for nutrition assessment and recommendations in consultations with patients.42 Thus, funding is an additional barrier to the implementation of nutrition advice during counselling as healthcare practitioners are not adequately reimbursed.8,22,27 Supplementary solutions for current time constraints include improved education concerning the delivery of brief interventions to promote healthy dietary behaviour change within the context of limited time or the collaboration with other staff that may increase practitioners’ time with patients.21 The challenge of prioritisation of nutrition is linked to the limited time in standard consultations with patients.13,27,28,35 Whilst increasing practitioners’ knowledge about the importance of nutrition interventions may encourage the provision of nutrition advice, the matter of time continues to lower the priority of nutrition over acute health-related problems.

Although many studies of the perspectives of nurses and doctors were identified, no articles reported on the opinions of dentists towards nutrition counselling. This is an unexpected finding as poor dietary habits are associated with poor dental outcomes, including cavities and gum disease, and poor dental conditions limit individuals food choices.43 Dental practitioners recognise the essential role of dietary counselling in the prevention of cavities, but infrequently provide brief and non-specific nutrition advice due to a perceived low level of confidence and competence.43 The literature also reported various challenges, including financial compensation, insufficient education and training, and time constraints.44 These findings coincide with the perspectives of other primary healthcare practitioners included in this review. Furthermore, only one study included in this review explored the perspectives of pharmacists toward nutrition and dietarycounselling.17 The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia’s National Competency Standard Framework indicates that the role of pharmacists encompasses the promotion of dietary recommendations that complements the provision of medications.45 In previous studies, it has been identified that pharmacists’ lack of knowledge and expertise in nutrition was a major limitation in providing dietary counselling.46,47 Additionally, pharmacists strongly agreed that they are an accessible and credible source of nutrition information for patients but reported low confidence in providing this nutrition-based therapy.48 Hence the perspectives of pharmacists and dentists align with the perspectives of primary healthcare practitioners explored in this review.

Although this study exclusively analysed the opinions of primary healthcare practitioners, dieticians are clearly specialists in providing detailed dietary advice. According to the Australian Government Department of Health, if an individual is diagnosed with a disease where nutrition plays an important role in disease management (e.g., cardiovascular disease or diabetes), general practitioners can provide a General Practitioner Management Plan (GPMP) and Team Care Arrangement (TCA), which entitles the individual to five visits per year to a registered dietician.49 However, patient access to dieticians may be limited due to socioeconomic factors, remote location, or patient’s health conditions not qualifying them for this rebate. In addition, the GPMP and TCA do not cover the entire cost of appointments, with out-of-pocket gaps having to be paid by patients.49 Previous reports highlight a shortage of dieticians in rural and regional areas where populations often demonstrate the greatest need for dietary interventions.6 Limitations that reduce access of patients to dieticians also include the low rate of referrals by practitioners such as physicians related to patient resistance given the cost of dietician services.50 Lastly, the role of nutrition in disease prevention is clearly as important as the role of dietary changes after patients are diagnosed with a chronic condition. Therefore, there is an increased obligation of primary healthcare practitioners to provide nutrition advice given their feasibility and accessibility, particularly in remote locations.

Limitations

Although a broad and comprehensive search of key databases was conducted, a perceived limitation of this study may have been the exclusion of the database CINAHL. CINAHL was excluded from the search strategy because it predominantly covers allied health practitioners. In addition, participant numbers were small in some of the articles included, in particular qualitative studies that used interviews and focus groups, which may have been due to data saturation. Lastly, convenience sampling was utilised in the majority of studies, which is common in this line of research.

Conclusions

This review has identified several key challenges that influence the provision of nutrition advice to patients by primary health care providers in Australia and New Zealand, including time constraints, insufficient education and training and associated factors such as low knowledge, confidence and low prioritisation of nutrition. There is clearly scope for improving medical education curricula in the area of nutrition counselling. Primary healthcare education needs to include curricula on evidence-based nutrition that can be implemented effectively within the time constraints of a standard consultation to allow adequate patient counselling in nutrition. This would also require further research to investigate whether brief dietary interventions with patients are indeed effective in improving patients’ dietary habits and nutritional status. Lastly, further research should investigate the perspectives of dentists and pharmacists toward nutrition counselling.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary file 1

Appendix 1. PRISMA flow diagram of literature search method (S1.pdf, 98 kb)References

- WHO. Nutrition for health and development: a global agenda for combating malnutrition, 2000. [Cited 20 December 2021]; Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66509.

- WHO. Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation – Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. Technical Report Series No. 916, 2003. [Cited 20 December 2021]; Available from: http://health.euroafrica.org/books/dietnutritionwho.pdf.

- Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, Cornaby L, Ferrara G and Salama JS, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2019; 393: 1958-1972.

Full Text PubMed - WHO. United Nations decade of action on nutrition (2016-2025) Work Program, 2017. [Cited 20 December 2021]; Available from: https://www.fao.org/3/bs726e/bs726e.pdf.

- Hogan S, Tuano K. NZIER Report to Dietietics NZ: A critical missing ingredient: the case for increased dietetic input in tier 1 health services, 2021. [Cited 20 December 2021]; Available from: https://dietitians.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Dietitians-NZ-Final-report.pdf.

- Siopis G, Jones A and Allman-Farinelli M. The dietetic workforce distribution geographic atlas provides insight into the inequitable access for dietetic services for people with type 2 diabetes in Australia. Nutr Diet. 2020; 77: 121-130.

Full Text PubMed - Crowley J, O'Connell S, Kavka A, Ball L and Nowson CA. Australian general practitioners' views regarding providing nutrition care: results of a national survey. Public Health. 2016; 140: 7-13.

Full Text PubMed - Cass S, Ball L and Leveritt M. Australian practice nurses' perceptions of their role and competency to provide nutrition care to patients living with chronic disease. Aust J Prim Health. 2014; 20: 203-208.

Full Text PubMed - Grant MJ and Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009; 26: 91-9108.

Full Text PubMed - Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101.

- Arrish J, Yeatman H and Williamson M. Australian midwives and provision of nutrition education during pregnancy: A cross sectional survey of nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and confidence. Women Birth. 2016; 29: 455-464.

Full Text PubMed - Arrish J, Yeatman H, Williamson M. Self-reported nutrition education received by Australian midwives before and after registration. J Preg. 2017;2017:5289592.

- Chapple LA, Chapman M, Shalit N, Udy A, Deane A, Williams L. Barriers to nutrition intervention for patients with a traumatic brain injury: views and attitudes of medical and nursing practitioners in the acute care setting. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2018;42:318-326.

- Crowley J, Ball L, Han DY, McGill AT, Arroll B, Leveritt M and Wall C. Doctors' attitudes and confidence towards providing nutrition care in practice: Comparison of New Zealand medical students, general practice registrars and general practitioners. J Prim Health Care. 2015; 7: 244-250.

PubMed - Crowley J, Ball L, McGill AT, Buetow S, Arroll B, Leveritt M and Wall C. General practitioners' views on providing nutrition care to patients with chronic disease: a focus group study. J Prim Health Care. 2016; 8: 357-364.

Full Text PubMed - Crowley J, Ball L and Wall C. Nutrition advice provided by general practice registrars: an investigation using patient scenarios. Public Health. 2016; 140: 17-22.

Full Text PubMed - El-Mani SF, Mullart J, Charlton KE, Flood VM. Folic acid and iodine supplementation during pregnancy: how much do pharmacists know and which products are readily available? J Pharm Pract Res. 2014;44:113-119.

- Fieldwick D, Smith A and Paterson H. General practitioners and gestational weight management. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019; 39: 485-491.

Full Text PubMed - Forsyth N, Elmslie J, Ross M. Supporting healthy eating practices in a forensic psychiatry rehabilitation setting. Nutr Diet. 2012;69:39-45.

- Lucas CJ, Charlton KE, Brown L, Brock E, Cummins L. Antenatal shared care: are pregnant women being adequately informed about iodine and nutritional supplementation? Aust New Zealand J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;54:515-521.

- Martin L, Leveritt MD, Desbrow B and Ball LE. The self-perceived knowledge, skills and attitudes of Australian practice nurses in providing nutrition care to patients with chronic disease. Fam Pract. 2014; 31: 201-208.

Full Text PubMed - Mitchell LJ, Macdonald-Wicks L and Capra S. Nutrition advice in general practice: the role of general practitioners and practice nurses. Aust J Prim Health. 2011; 17: 202-208.

Full Text PubMed - Morphet J, Clarke AB and Bloomer MJ. Intensive care nurses' knowledge of enteral nutrition: a descriptive questionnaire. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2016; 37: 68-74.

Full Text PubMed - Nowson CA, O’Connell SL. Nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and confidence of Australian general practice registrars. J Biomed Edu. 2015;2015:219198.

- Parry Strong A, Lyon J, Stern K, Vavasour C and Milne J. Five-year survey of Wellington practice nurses delivering dietary advice to people with type 2 diabetes. Nutr Diet. 2014; 71: 22-27.

Full Text - Puhringer PG, Olsen A, Climstein M, Sargeant S, Jones LM and Keogh JW. Current nutrition promotion, beliefs and barriers among cancer nurses in Australia and New Zealand. PeerJ. 2015; 3: 1396.

Full Text PubMed - Waterland JL, Edbrooke L, Appathurai A, Lawrance N, Temple-Smith M and Denehy L. 'Probably better than any medication we can give you': General practitioners' views on exercise and nutrition in cancer. Aust J Gen Pract. 2020; 49: 513-518.

Full Text PubMed - Whitelock G and Kapur E. Interns' knowledge of, and attitudes and practices towards malnutrition and hydration in an Australian acute tertiary-care hospital. Australasian Medical Journal. 2018; 11: 397-405.

Full Text - Winter J, McNaughton SA and Nowson CA. Nutritional care of older patients: experiences of general practitioners and practice nurses. Aust J Prim Health. 2017; 23: 178-182.

Full Text PubMed - Ball LE, Hughes RM and Leveritt MD. Nutrition in general practice: role and workforce preparation expectations of medical educators. Aust J Prim Health. 2010; 16: 304-310.

Full Text PubMed - Kolasa KM and Rickett K. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling cited by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010; 25: 502-509.

Full Text PubMed - Wynn K, Trudeau JD, Taunton K, Gowans M and Scott I. Nutrition in primary care: current practices, attitudes, and barriers. Can Fam Physician. 2010; 56: 109-116.

PubMed - WHO. Nutrition, 2021. [Cited 20 December 2021]; Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/nutrition.

- Marshall AP, Takefala T, Williams LT, Spencer A, Grealish L and Roberts S. Health practitioner practices and their influence on nutritional intake of hospitalised patients. Int J Nurs Sci. 2019; 6: 162-168.

Full Text PubMed - Arrish J, Yeatman H and Williamson M. Nutrition education in Australian midwifery programmes: a mixed-methods study. J Biomed Edu. 2016; 9680430: 1-12.

Full Text - Görig T, Mayer M, Bock C, Diehl K, Hilger J, Herr RM and Schneider S. Dietary counselling for cardiovascular disease prevention in primary care settings: results from a German physician survey. Fam Pract. 2014; 31: 325-332.

Full Text PubMed - Adamski M, Gibson S, Leech M and Truby H. Are doctors nutritionists? What is the role of doctors in providing nutrition advice? Nutr Bull. 2018; 43: 147-152.

Full Text - Nowson C. Nutrition Competency Framework 2016. [Cited 01 November 2021]; Available from: https://www.deakin.edu.au/students/faculties/faculty-of-health/school-of-exercise-and-nutrition-sciences/research/wncit/toolkit/nutrition-competency-framework.

- Crowley J, Ball L, Laur C, Wall C, Arroll B, Poole P and Ray S. Nutrition guidelines for undergraduate medical curricula: a six-country comparison. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015; 6: 127-133.

Full Text PubMed - Lepre B, Mansfield KJ, Ray S and Beck E. Reference to nutrition in medical accreditation and curriculum guidance: a comparative analysis. BMJ Nutr Prev Health. 2021; 4: 307-318.

Full Text PubMed - Crowley J, Ball L and Hiddink GJ. Nutrition in medical education: a systematic review. Lancet Planet Health. 2019; 3: 379-389.

Full Text PubMed - Nicholas LG, Pond CD and Roberts DC. Dietitian-general practitioner interface: a pilot study on what influences the provision of effective nutrition management. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003; 77: 1039-1042.

Full Text PubMed - Hayes MJ, Cheng B, Musolino R and Rogers AA. Dietary analysis and nutritional counselling for caries prevention in dental practise: a pilot study. Aust Dent J. 2017; 62: 485-492.

Full Text PubMed - Franki J, Hayes MJ and Taylor JA. The provision of dietary advice by dental practitioners: a review of the literature. Community Dent Health. 2014; 31: 9-14.

PubMed - Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. National competency standards framework for pharmacists in Australia, 2016. [Cited 04 June 2021]; Available from: https://my.psa.org.au/s/article/2016-Competency-Framework.

- Kwan D, Hirschkorn K and Boon H. U.S. and Canadian pharmacists' attitudes, knowledge, and professional practice behaviors toward dietary supplements: a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006; 6: 31.

Full Text PubMed - Medhat M, Sabry N and Ashoush N. Knowledge, attitude and practice of community pharmacists towards nutrition counseling. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020; 42: 1456-1468.

Full Text PubMed - Douglas PL, McCarthy H, McCotter LE, Gallen S, McClean S, Gallagher AM and Ray S. Nutrition education and community pharmacy: a first exploration of current attitudes and practices in Northern Ireland. Pharmacy (Basel). 2019; 7: .

Full Text PubMed - Australian Government Department of Health. CDM individual allied health services provider information, 2013. [Cited 05 June 2021]; https://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/212786/MBS_Chronic_Disease_Management_and_Allied_Health_Fact_Sheet.pdf.

- Mulquiney KJ, Tapley A, van Driel ML, Morgan S, Davey AR, Henderson KM, Spike NA, Kerr RH, Watson JF, Catzikiris NF and Magin PJ. Referrals to dietitians/nutritionists: a cross-sectional analysis of Australian GP registrars' clinical practice. Nutr Diet. 2018; 75: 98-9105.

Full Text PubMed