Virtual global health in graduate medical education: a systematic review

Lisa Umphrey1, Nora Lenhard2, Suet Kam Lam3, Nathaniel E. Hayward4, Shaina Hecht5, Priya Agrawal6, Amy Chambliss1, Jessica Evert7, Heather Haq8, Stephanie M. Lauden9, George Paasi10, Mary Schleicher11 and Megan Song McHenry6

1Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA

2Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA

3Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA

4Department of Pediatrics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

5Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA

6Mid-Atlantic Permanente Medical Group, Washington, DC, USA

7Child Family Health International, El Cerrito, California, USA

8Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Texas, USA

9Nationwide Children's Hospital, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

10Mbale Clinical Research Institute, Mbale, Uganda

11Cleveland Clinic Floyd D. Loop Alumni Library, Cleveland, OH, USA

Submitted: 12/02/2022; Accepted: 04/08/2022; Published: 31/08/2022

Int J Med Educ. 2022; 13:230-248; doi: 10.5116/ijme.62eb.94fa

© 2022 Lisa Umphrey et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use of work provided the original work is properly cited. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0

Abstract

Objectives: To synthesize recent virtual global health education activities for graduate medical trainees, document gaps in the literature, suggest future study, and inform best practice recommendations for global health educators.

Methods: We systematically reviewed articles published on virtual global health education activities from 2012-2021 by searching MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, ERIC, Scopus, Web of Science, and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I. We performed bibliography review and search of conference and organization websites. We included articles about primarily virtual activities targeting for health professional trainees. We collected and qualitatively analyzed descriptive data about activity type, evaluation, audience, and drivers or barriers. Heterogeneity of included articles did not lend to formal quality evaluation.

Results: Forty articles describing 69 virtual activities met inclusion criteria. 55% of countries hosting activities were high-income countries. Most activities targeted students (57%), with the majority (53%) targeting trainees in both low- to middle- and high-income settings. Common activity drivers were course content, organization, peer interactions, and online flexibility. Common challenges included student engagement, technology, the internet, time zones, and scheduling. Articles reported unanticipated benefits of activities, including wide reach; real-world impact; improved partnerships; and identification of global health practice gaps.

Conclusions: This is the first review to synthesize virtual global health education activities for graduate medical trainees. Our review identified important drivers and challenges to these activities, the need for future study on activity preferences, and considerations for learners and educators in low- to middle-income countries. These findings may guide global health educators in their planning and implementation of virtual activities.

Introduction

Global health (GH), a rapidly growing field focused on advancing international and interdisciplinary healthcare1-12 while addressing health inequities,13 is an increasingly common component of graduate medical education and international partnerships.1,14 The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted in-person GH education (GHE) activities such as international clerkships and rotations15, 16 and worsened inherent inequities in GH.17, 18 Typical challenges encountered in GHE work, including distance, communication, and barriers to bidirectional exchange of staff and learners 6 worsened throughout the pandemic,19, 20 highlighting the need for thoughtful development of virtual GH curricula and practice.

Since the start of the pandemic, much has been published on shifting graduate medical education activities into the virtual realm, but little research focuses on virtual approaches to GHE, particularly within GH partnerships where barriers such as poor internet access persist.14, 21-23 While several papers discuss the use of virtual education for GH preparation, simulation, and education,7, 24-29 ethical considerations in GH engagement,30-32 and clear learner competencies for GHE within GH partnerships,1, 24, 25, 27, 28 limited guidance exists regarding methods to virtually sustain or improve formerly in-person GHE activities during the pandemic or similar disruptive global challenges. Few previous papers focus on supporting partners in low- to middle-income countries (LMIC) during times of crisis,26, 33 and it is unclear how GH competencies can be reinforced virtually for learners in high income countries (HIC) while prioritizing the needs of partners in LMIC.20,21,34,35 Last, to our knowledge no current studies examine faculty or learner preferences for virtual GHE activities (VGHEAs).

Virtual GH content is necessary and relevant now due to current travel restrictions, but this mode of engagement will undoubtedly be a key component of GHE moving forward. 15 Hindrances from financial constraints, ongoing travel restrictions, threats of future COVID-19 variants, and equitable access to vaccination may continue to limit in-person GHE activities.19,20 VGHEAs may provide the GH community with lower cost, more attainable engagement strategies, and may facilitate mutual learning, goal setting, and problem solving.

There is a crucial need for evidence about VGHEA planning, implementation, and continuation, particularly regarding the specific needs of learners in LMICs, to guide GH educators and the creation of GH programming. This systematic review, therefore, aimed to identify and synthesize recent VGHEAs (including their enablers and barriers) targeting health professional trainees of any level, to document gaps in the existing literature, to identify areas of future study, and to contribute to preliminary foundational data to inform future best practice recommendations for GH educators.

Methods

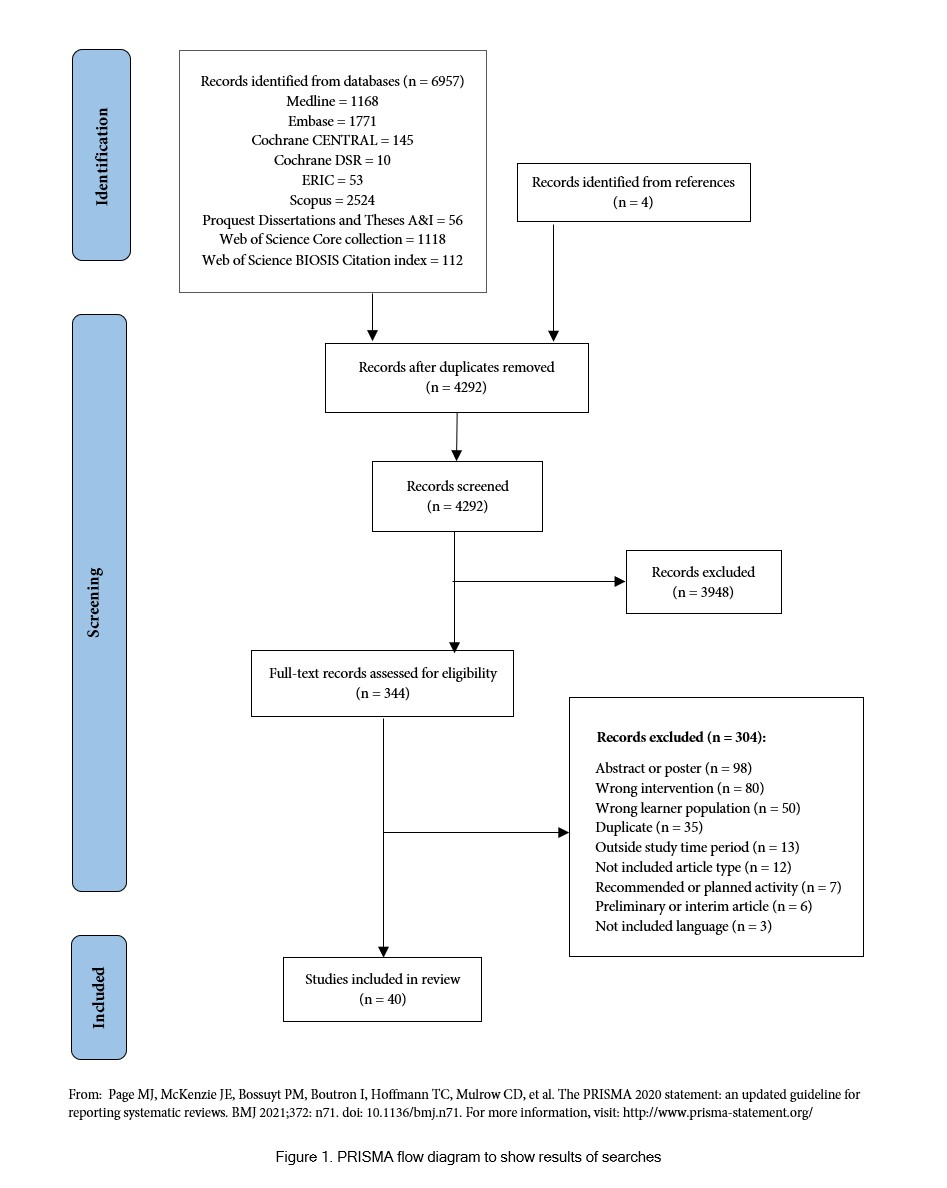

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Protocols 2015 Checklist36 to perform our systematic review, which we chose as the most appropriate methodology to summarize recent VGHEAs over our review period. We registered the general systematic review protocol with PROSPERO on February 14th, 2021.37 Ethical approval was not required for our review.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion in this review required that articles from the primary literature between 2012-2021 focus on existing and sustained GH curricula, programs, activities, or online content. Our definition of “GH content” included any activity highlighting health disparities due to resource level, geography, or access to care. The administration of the GH content had to be primarily virtual, not supplementary to an in-person activity. The target users of the content had to be health professional trainees of any level or specialty. We chose to include articles between 2012-2021 to focus our evaluation on more recent technology and on articles with more robust descriptions of virtual activities.

Our review excluded online content not otherwise described in the primary literature; general open access resources without a stated objective to reach trainees in under-resourced or LMIC settings; descriptions of telemedicine services; and non-human GH topics. If multiple papers described the VGHEA, our review included only the most recent article. Our review also excluded Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) 38 discussions, as they are not trainee-focused and were outside the scope of this manuscript. Please see Appendix 1 for full inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Search strategy

A medical librarian (M.S.) constructed a comprehensive search strategy to capture the concept of VGHEAs (Appendix 2). We used the strategy to search the following databases on November 4, 2021: Ovid MEDLINE®, Ovid Embase, Cochrane Library from Wiley, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC, via EBSCO interface), Scopus via Elsevier, Web of Science from Clarivate Analytics, and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I. One co-author (N.E.H.) searched the grey literature sites per the strategy in Appendix 2. Two authors (N.L. and L.U.) also reviewed the references for pertinent articles.

Article selection

We used Covidence software39 to manage the systematic review process. Two reviewers (L.U. and N.L.) performed the initial article screening by assessing titles and abstracts from the search. Article exclusion occurred if they lacked a GHE or virtual focus. After the initial exclusion process, L.U. and N.L. independently reviewed the full text of the remaining articles to determine whether articles met the predetermined eligibility criteria. Because the heterogeneity of articles included did not lend to formal quality evaluation, we jointly determined our parameters for making judgements and used three general ratings. “Good” and “fair” articles met inclusion criteria and included information on at least >75% or 50-75%, respectively, of planned data extraction points. “Poor” articles did not adequately meet inclusion criteria and/or did not contain sufficient information for data extraction. We included “good” articles, excluded “poor” articles, and further discussed “fair” articles to reach consensus. A third reviewer (S.K.L.) settled disagreements on inclusion or exclusion via collaborative consultation.

Data extraction

Members of the study team independently extracted data from the articles in an Excel spreadsheet. Three reviewers (L.U., N.L. and N.E.H.) then cross-checked extracted data. Extracted data included: activity type, synopsis, ownership, length, frequency, content delivery, cost, evaluation, outcomes; targeted participant type, numbers, and location; drivers/enablers, barriers/challenges, and impact. We organized the VGHEAs into 8 activity types: synchronous activities (e.g., discussions, conferences, chats, skills sessions, simulations, or lectures); asynchronous activities (e.g., modules, videos, or pre-recorded lectures); group learning or projects; shared cloud resources; complete online GH courses; virtual mentorship; paired learning (“twinning”) experiences; and online discussion forums.

Data synthesis and analysis

We performed a qualitative summary of the data given the nature of the systematic review and the preponderance of descriptive statistics in included papers. We summarized descriptive data, identified common collective themes, and noted gaps in available information.

Results

Database searches identified a total of 6,957 references. Covidence removed 2,669 duplicates, leaving 4,288 citations for title and abstract screening. Forty articles were found to be of relevance to this review (Figure 1).

General descriptions of VGHEA articles

Table 1 provides general descriptions of the 40 included articles, including descriptions of 69 different VGHEAs. Many articles (48%, 19/40) described newly formed VGHEAs existing for < 1 year. The most common format of VGHEAs (25%, 10/40 of included papers) utilized regularly available online content or short courses in GH. Most articles (70%, 28/40) reported online-only activities, while 30% (12/40) reported hybrid or blended activities that included both online and in-person components. Most activities (48%, 19/40) were synchronous, 30% (12/40) were asynchronous, 17% (7/40) were both, and 5% (2/40) were downloadable materials only. Most activities (65%, 26/40) were available through a university, with smaller subsets being available through a GH partner (13%, 6/40) or via open access online (10%, 4/40). One article (3%, 1/40) reported requiring payment for the activity, and another (3%, 1/40) reported detailed activity cost information.

Types of VGHEAs

Most included articles (57%, 23/40) described multiple VGHEAs. The VGHEA activity types are as follows: synchronous activities (93%, 47/40 of articles); asynchronous activities (35%, 14/40); group learning or projects (23%, 9/40 of articles); shared cloud resources (15%, 6/40 of articles); complete GH courses (15%, 6/40 of articles); virtual mentorship (10%, 4/40 of articles); twinning experiences (5%, 2/40 of articles); and online discussion forums (10%, 4/40 of articles).

Topic/focus of VGHEA

The complete list of topics covered in the described VGHEAs are listed in Table 1. Most articles (68%, 27/40) focused on general GH topics (e.g., global health education, community health, or field experiences) while 32% (13/40) focused on GH topics linked to a medical specialty (e.g., anesthesia or surgical training in LMICs). While the vast majority (95%, 38/40) of articles focused on international GH, two articles (5%, 2/40) focused on local GH. One paper (3%, 1/40) had health equity and equitable partnerships as a key focus.

Trainee audience

Approximately 8400 total trainees were described in the included articles; one study (3%, 1/40) included 6000 trainees, and the remaining papers reported 11-501 trainees (mean 84). Targeted trainees were graduate medical students (57%, 23/40 of articles) or mixed audiences of health professional trainees (students, residents, or fellows) (33%, 13/40 of articles). Most articles (53%, 21/40) targeted trainees in both LMIC and HIC, while remaining articles reported targeting LMIC (22%, 9/40) or HIC (25%, 10/40) trainees alone.

Overall, few articles (10%, 4/40) reported details about trainee characteristics and rates of activity completion. One article (3%, 1/40) documented dropout rate of trainees through duration of the program, another (3%, 1/40) reported a documented increased participation rate over a two-year period during the activity, and two papers (5%, 2/40) provided a comparison of participation rates between trainees from HIC versus LMIC.

Evaluation and outcomes of VGHEAs

Most articles (90%, 36/40) discussed VGHEA evaluations. The most reported evaluation method was participant surveys (57%, 23/40 of articles). Different outcome measures discussed are available in Table 1, the most common being satisfaction with course, content, or teaching (60%, 24/40 of articles) and self-reported improvement in knowledge or skills (40%, 16/40 of articles). Detailed evaluation methods, however, were not a common feature of included articles.

Ownership and hosting of VGHEAs

Articles described a total of 31 countries (45%, 14/31 LMIC and 55%, 17/31 HIC) as hosts of the VGHEA(s). Most articles (68%, 27/40) reported hosting of the VGHEA by an individual institution, most commonly one within a HIC (65%, 26/40). One paper (3%, 1/40) reported a LMIC (Mexico) as the sole host, and no articles reported shared hosting between LMIC/LMIC partners.

Regarding authorship of included papers, 55% (22/40) had only authors from HIC institutions while 45% (18/40) had authors from both HIC and LMIC institutions.

No papers had only authors from LMIC institutions. Among the 18 articles with a mixed author group, 78% (14/18) had more HIC than LMIC authors; 11% (2/18) had more LMIC than HIC authors; and 11% (2/18) had equal numbers of LMIC and HIC authors. 92% (37/40) of articles had a HIC first author, and 90% (36/40) had a HIC last author.

Participation in VGHEAs

The 40 included articles described 66 countries (73%, 48/66 LMIC and 27%, 18/66 HIC) as having participated in the VGHEAs. A HIC (USA) was the most frequent consumer of VGHEAs, followed by India, the UK and Uganda.

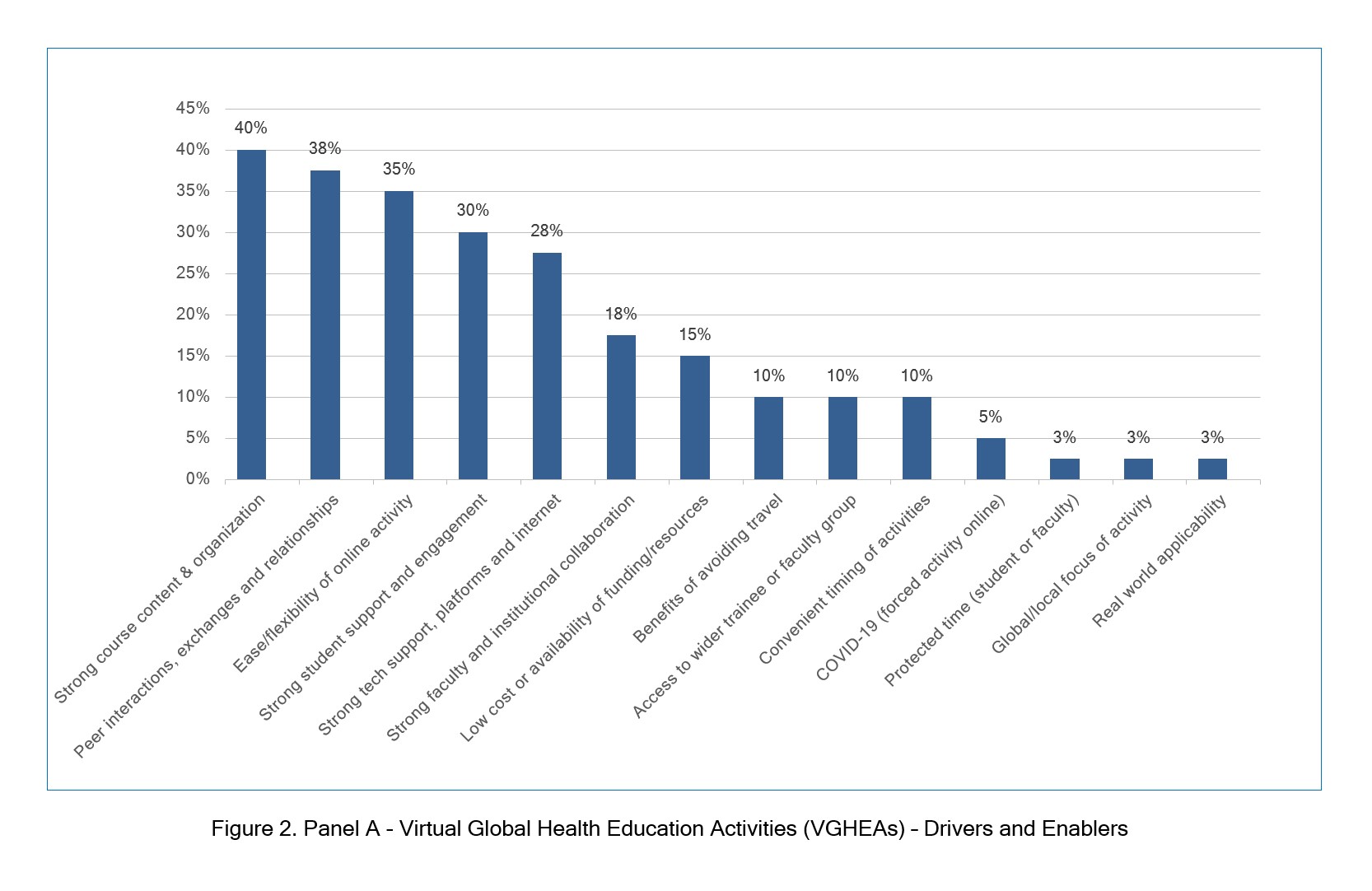

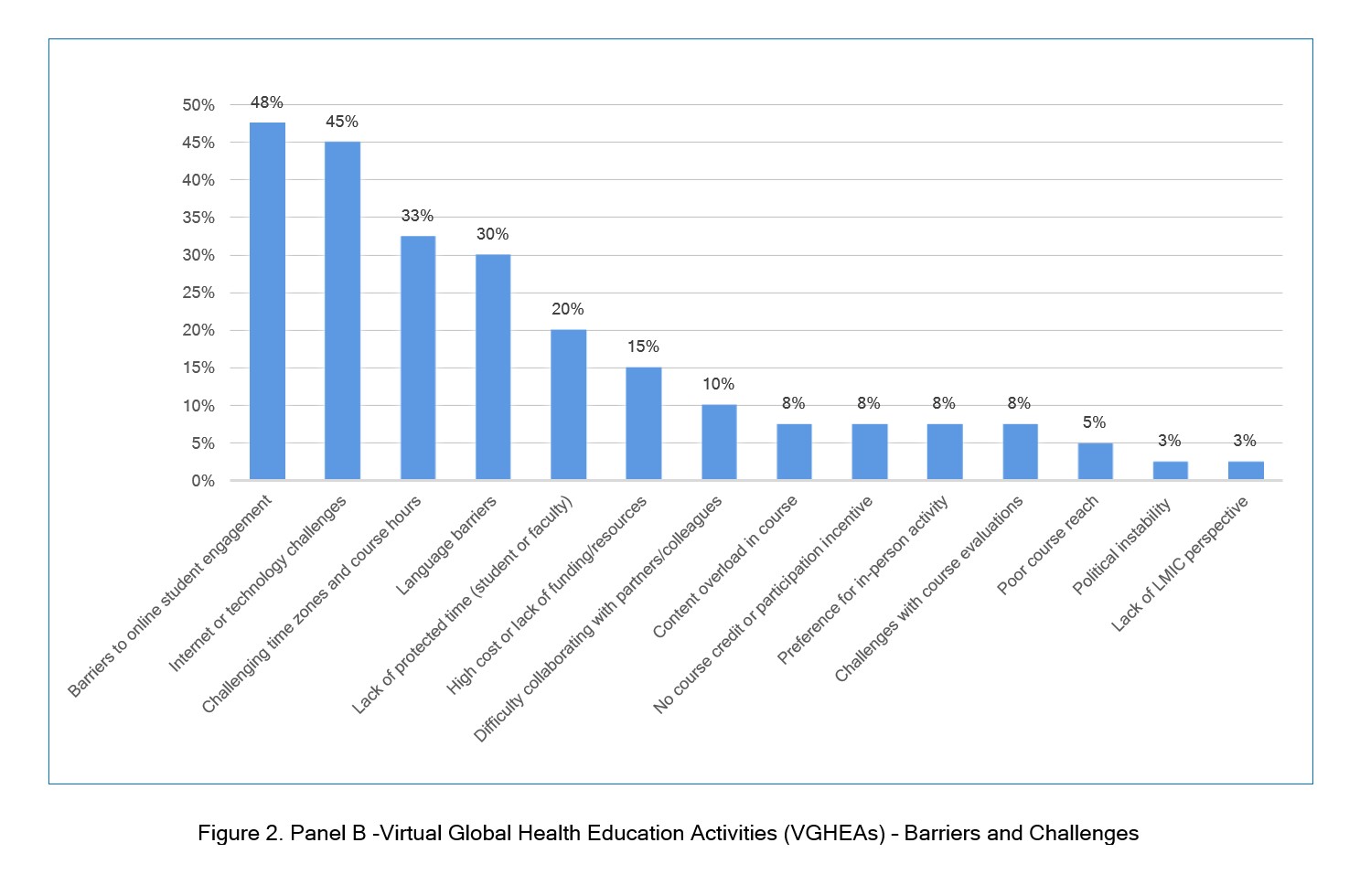

Drivers/enablers and barriers/challenges of VGHEAs

Most papers discussed drivers/enablers (93%, 37/40) and barriers/challenges (98%, 39/40) of VGHEAs (Figure 2, Panel A and B, respectively), which we grouped into 14 categories each. The most common drivers/enablers were strong course content and organization (40%, 16/40 of articles); peer interactions (38%, 15/40 of articles); and activity ease/flexibility (30%, 12/40 of articles). The most common barriers/challenges were challenges to online trainee engagement (unequal participation/engagement or lack of interest/motivation; 48%, 19/40 of articles); issues with virtual platforms/technology or internet connectivity problems (45%, 18/40 of articles); and challenges with time zones or course hours (33%, 13/40 of articles).

Unexpected impact of the course (positive or negative) and wider benefits noted:

Overall, 58% (23/40) of included articles cited a wider positive impact of the VGHEA beyond what was originally expected. Table 2 presents common themes, such as a wider reach than in-person activities, real world impact, improved existing GH partnerships and activities, and newly identified gaps in GH practices.

Notably, one article (3%, 1/40) cited unanticipated negative consequences of the VGHEA, specifically that uncertainties for ongoing funding and lack of foreign recognition of course credit were unexpected hardships for course participants.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to identify and synthesize the recent landscape of VGHEAs, including their enablers and barriers. The findings in this review identify gaps in the literature needing future study and illustrate important themes that GH educators should consider when planning and developing VGHEAs.

Most of the VGHEAs described no cost participation or content, but importantly, most articles implied that participation was linked to university tuition or membership or only available via a GH partnership. These findings highlight the difficulty in accessing VGHEAs should a learner not be affiliated with a university or formal GH program or partnership. Aside from one paper, 40 there was a paucity of information regarding specific costs of the activities, both in terms of host cost (e.g., technology infrastructure, platform subscriptions, salary support, etc.) and trainee costs (e.g., university fees, personal costs, cost of data plans or Wi-Fi to access, etc.). Because GH experiences are linked with increased awareness of health system costs and issues, and because decreased funding for GH activities could lead to negative consequences for education, partnerships, and collaboration (disproportionately affecting LMIC partners), 6, 40-43 more financial information about VGHEAs would be useful to inform the discussion on the costs and benefits of continuing in-person travel for GH activities versus shifting to virtual activities long-term.

In terms of ownership and hosting of VGHEAs, there was a notable lack of both shared hosting between LMIC partners and of LMIC institutions that had sole hosting/ownership of the activity. Regarding participation, the USA was overall the biggest consumer of activities reported, but it was unclear from papers discussing participation in VGHEAs by multiple countries what proportion of participants came from HIC versus LMIC settings. These findings raise multiple questions for future study regarding who is making decisions about content topics, target audiences, and goals of GH activities; whether virtual iterations of activities are appropriate for different audience types; and what barriers the HIC partner can alleviate for the LMIC partner.40 Regarding authorship, the vast majority of included papers reflected first and last authors from HIC institutions and an overall majority of HIC authors. Although this trend of unequal representation of LMIC authors in the GH literature is documented,44, 45 it is perhaps a call to colleagues involved in GH partnerships to ensure equal ownership and authorship of the VGHEA content and academic outputs.

Regarding targeted audiences, our team found surprisingly minimal information about the trainees in the included papers. Further elucidation of learner types and geographic distribution would be key in future studies to better understand activity uptake and appropriateness, particularly for unique LMIC learners, such as in refugee settings. 46 We also found that HIC audiences made up a larger proportion of targeted trainees. This merits further discussion in terms of how much content should be directed toward HIC consumers (specifically when the education is preparing for HIC trainees for experiences in LMIC settings) versus content focusing on building support for LMIC partners and addressing health disparities.

Included articles discussed VGHEA evaluations and measured various outcomes, but details about the evaluation methods were not always well described, nor were outcomes standard even among similar activities. Key gaps in our included literature sample appear to be standard evaluation tools, how to best document VGHEA effectiveness, and critically, how the VGHEA affects relevant communities after trainees completed the activity. Documenting and exploring these topics could have large implications for GH educators seeking concrete guidance on best practices for VGHEA evaluation and quality improvement.

The several enablers and barriers of VGHEAs and key themes identified provide important considerations for GH educators. Certain elements were both enablers and barriers, specifically funding, the need for protected and convenient course timing, and technological support needed for VGHEA implementation. The double mention of these factors highlights their critical importance to the success of VGHEAs; indeed, those articles that mentioned funding,47-52 timing,40, 53-55 and strong technology40, 49, 53, 54, 56-62 as facilitators of VGHEAs offer key insights into how to overcome barriers that may prevent successful VGHEA implementation. More research in this area will be important to guide the planning and development of VGHEAs, particularly between HIC/LMIC partners who will have different needs and capacities.

Our group noted several gaps in the available literature that could benefit from future study to better guide GH educators in their virtual program planning. In terms of the VGHEAs described in the 40 unique articles, we found that most papers provided basic, descriptive information only. While this information is useful to document the current landscape of VGHEAs, there was less information regarding best practice recommendations for described activities, specifically in terms of frequency, evaluation, duration, organization, and content. Additionally, included articles addressed a wide range of VGHEAs covering multiple topics. Further discussion is warranted on what types of activities work best in certain contexts and for which type of trainees. Virtual domestic or global-local activities, an important subject mentioned in only two articles,63,64 likewise merits future discussion. Last, there was a dearth of information on sustained virtual engagements to benefit ongoing GH partnerships, particularly for partners in LMICs. Only one paper 65 mentioned health equity and equitable partnerships as a topic area, specifically suggesting the need to have an indigenous perspective included in the course presentation. In the future, it will be important to discuss who decides on the topics included in each activity, particularly for those in LMIC consuming material made by HIC educators. Over the coming years, these considerations may influence virtual GHE planning and implementation at graduate medical institutions worldwide.

Our review had several limitations. First, authors attempted to identify all relevant VGHEA articles, but many initiatives prompted by the pandemic were most likely underway but not yet published. Second, we only included VGHEAs focusing on health professional trainees; future investigation into how community health workers or health professions engage with VGHEAs could be of benefit. Third, although the grey literature search found no additional articles to be screened after cross-referencing article databases and online repositories, we found but excluded an abundance of GH activities (typically on websites, in conference proceedings and abstracts, and on online discussion forums) without a link to primary literature; a future mapping of these resources would be useful. Lastly, the broad nature of GHE introduces the possibility of bias in how we defined an activity and decided on inclusion. Addressing these limitations in future reviews would further contribute to guidelines for graduate GH educators.

Conclusions

Our systematic review is the first review to identify and synthesize recent VGHEAs and report on the drivers and barriers that exist in the current literature. The field of VGHEA remains heterogenous and few studies aimed to examine best practices in the development of VGHEA. With medical trainees from HIC being the primary consumer of VGHEA, further consideration on how to be meet the needs of LMIC trainees is needed. These insights may provide guidance to GH educators in their planning and implementation of VGHEAs moving forward. Further work is needed on activity preferences, considerations for LMIC learners, best practice recommendations, and how activities could be created, shared, and consumed more equitably by partners from both HIC and LMIC settings. This review contributes meaningful foundational data to guide discussions among GH educators to address these knowledge gaps.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Geoffrey Winstanley for his assistance in the creation of included figures.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary file 1

Appendix 1 Virtual global health education activity review inclusion and exclusion criteria (S1.pdf, 107 kb)Supplementary file 2

Appendix 2 Complete search strategies (S2.pdf, 56 kb)References

- Steenhoff AP, Crouse HL, Lukolyo H, Larson CP, Howard C, Mazhani L, Pak-Gorstein S, Niescierenko ML, Musoke P, Marshall R, Soto MA, Butteris SM and Batra M. Partnerships for global child health. Pediatrics. 2017; 140: e20163823.

Full Text PubMed - Rowthorn V. Global/local: what does it mean for global health educators and how do we do it? Ann Glob Health. 2015; 81: 593-601.

Full Text PubMed - Beaglehole R and Bonita R. What is global health? Glob Health Action. 2010; 3: 5142.

Full Text PubMed - Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, Reddy KS, Rodriguez MH, Sewankambo NK and Wasserheit JN. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009; 373: 1993-1995.

Full Text PubMed - Fried LP, Bentley ME, Buekens P, Burke DS, Frenk JJ, Klag MJ and Spencer HC. Global health is public health. Lancet. 2010; 375: 535-537.

Full Text PubMed - Pitt MB, Gladding SP, Majinge CR and Butteris SM. Making global health rotations a two-way street: a model for hosting international residents. Glob Pediatr Health. 2016; 3: 2333794-23337916630671.

Full Text PubMed - Batra M, Pitt MB, St Clair NE and Butteris SM. Global health and pediatric education: opportunities and challenges. Adv Pediatr. 2018; 65: 71-87.

Full Text PubMed - Editors MEDICC Review. Closing the "know-do" gap: eHealth strategies for the global south. Int Health. 2008; 10: 3.

Full Text PubMed - Abimbola S. On the meaning of global health and the role of global health journals. Int Health. 2018; 10: 63-65.

Full Text PubMed - Campbell RM, Pleic M and Connolly H. The importance of a common global health definition: how Canada's definition influences its strategic direction in global health. J Glob Health. 2012; 2: 010301.

Full Text PubMed - Frenk J, Gómez-Dantés O and Moon S. From sovereignty to solidarity: a renewed concept of global health for an era of complex interdependence. Lancet. 2014; 383: 94-97.

Full Text PubMed - King NB and Koski A. Defining global health as public health somewhere else. BMJ Glob Health. 2020; 5: 002172.

Full Text PubMed - Farmer PE, Furin JJ and Katz JT. Global health equity. Lancet. 2004; 363: 1832.

Full Text PubMed - Rees CA, Keating EM, Dearden KA, Haq H, Robison JA, Kazembe PN, Bourgeois FT and Niescierenko M. Improving pediatric academic global health collaborative research and agenda setting: a mixed-methods study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020; 102: 649-657.

Full Text PubMed - Conway JH, Machoian RG, Olsen CW. Issues concerning overseas travel that international educators must consider in the coming months (opinion). 2021.

- Weine S, Bosland M, Rao C, Edison M, Ansong D, Chamberlain S and Binagwaho A. Global health education amidst covid-19: disruptions and opportunities. Ann Glob Health. 2021; 87: 12.

Full Text PubMed - Karim N, Rybarczyk MM, Jacquet GA, Pousson A, Aluisio AR, Bilal S, Moretti K, Douglass KA, Henwood PC, Kharel R, Lee JA, MenkinSmith L, Moresky RT, Gonzalez Marques C, Myers JG, O'Laughlin KN, Schmidt J and Kivlehan SM. COVID-19 pandemic prompts a paradigm shift in global emergency medicine: multidirectional education and remote collaboration. AEM Educ Train. 2021; 5: 79-90.

Full Text PubMed - Shamasunder S, Holmes SM, Goronga T, Carrasco H, Katz E, Frankfurter R and Keshavjee S. COVID-19 reveals weak health systems by design: why we must re-make global health in this historic moment. Glob Public Health. 2020; 15: 1083-1089.

Full Text PubMed - Chatziralli I, Ventura CV, Touhami S, Reynolds R, Nassisi M, Weinberg T, Pakzad-Vaezi K, Anaya D, Mustapha M, Plant A, Yuan M and Loewenstein A. Transforming ophthalmic education into virtual learning during COVID-19 pandemic: a global perspective. Eye (Lond). 2021; 35: 1459-1466.

Full Text PubMed - Kalbarczyk A, Harrison M, Sanguineti MCD, Wachira J, Guzman CAF and Hansoti B. Practical and ethical solutions for remote applied learning experiences in global health. Ann Glob Health. 2020; 86: 103.

Full Text PubMed - Ambrose M, Murray L, Handoyo NE, Tunggal D and Cooling N. Learning global health: a pilot study of an online collaborative intercultural peer group activity involving medical students in Australia and Indonesia. BMC Med Educ. 2017; 17: 10.

Full Text PubMed - Barteit S, Sié A, Yé M, Depoux A, Louis VR and Sauerborn R. Lessons learned on teaching a global audience with massive open online courses (MOOCs) on health impacts of climate change: a commentary. Global Health. 2019; 15: 52.

Full Text PubMed - Brzoska P, Akgün S, Antia BE, Thankappan KR, Nayar KR and Razum O. Enhancing an international perspective in public health teaching through formalized university partnerships. Front Public Health. 2017; 5: 36.

Full Text PubMed - Ahrens K, Stapleton FB and Batra M. The university of washington pediatric residency program experience in global health and community health and advocacy. Virtual Mentor. 2010; 12: 184-189.

Full Text PubMed - DeCamp M, Rodriguez J, Hecht S, Barry M and Sugarman J. An ethics curriculum for Short-Term Global Health trainees. Global Health. 2013; 9: 5.

Full Text PubMed - McQuilkin P, Marshall RE, Niescierenko M, Tubman VN, Olson BG, Staton D, Williams JH and Graham EA. A successful us academic collaborative supporting medical education in a postconflict setting.

Glob Pediatr Health. 2014; 1: 2333794-23337914563383.

Full Text PubMed - Shah S, Lin HC and Loh LC. A comprehensive framework to optimize Short-Term Experiences in Global Health (STEGH). Global Health. 2019; 15: 27.

Full Text PubMed - Global health education competencies toolkit. consortium of universities for global health, 2018. [Cited 15 January 2022]; Available from: https://www.cugh.org/online-tools/competencies-toolkit/.

- Frehywot S, Vovides Y, Talib Z, Mikhail N, Ross H, Wohltjen H, Bedada S, Korhumel K, Koumare AK and Scott J. E-learning in medical education in resource constrained low- and middle-income countries. Hum Resour Health. 2013; 11: 4.

Full Text PubMed - Crump JA and Sugarman J. Ethics and best practice guidelines for training experiences in global health. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010; 83: 1178-1182.

Full Text PubMed - Evert J. Teaching corner: child family health international : the ethics of asset-based global health education programs. J Bioeth Inq. 2015; 12: 63-67.

Full Text PubMed - Rowthorn V, Loh L, Evert J, Chung E and Lasker J. Not above the law: a legal and ethical analysis of Short-Term Experiences in Global Health. Ann Glob Health. 2019; 85: 79.

Full Text PubMed - McQuilkin PA, Niescierenko M, Beddoe AM, Goentzel J, Graham EA, Henwood PC, Rehwaldt L, Teklu S, Tupesis J and Marshall R. Academic medical support to the Ebola virus disease outbreak in Liberia. Acad Med. 2017; 92: 1674-1679.

Full Text PubMed - Amerson R. Striving to meet global health competencies without study abroad. J Transcult Nurs. 2021; 32: 180-185.

Full Text PubMed - World Bank Country and Lending Groups, 2022. World Bank, Washington DC, USA. [Cited 15 January 2021]; Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P and Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2021; 74: 790-799.

Full Text PubMed - Umphrey L, Lenhard N, Lam S, Schleicher M, Lauden S, Haq H, et al. Virtual global health education: a systematic review. PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021228600]. [Cited 10 February 2022]; Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021228600.

- Project ECHO. University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2022. [Cited 13 January 2022]; Available from: https://hsc.unm.edu/echo/.

- Covidence systematic review software. Veritas health innovation, Melbourne, Australia, 2022. [Cited 15 January 2022]; Available from: https://www.covidence.org/.

- Jiang LG, Greenwald PW, Alfonzo MJ, Torres-Lavoro J, Garg M, Munir Akrabi A, Sylvanus E, Suleman S and Sundararajan R. An international virtual classroom: the emergency department experience at Weill Cornell Medicine and Weill Bugando medical center in Tanzania. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2021; 9: 690-697.

Full Text PubMed - Lanys A, Krikler G and Spitzer RF. The impact of a global health elective on CanMEDS competencies and future practice. Hum Resour Health. 2020; 18: 6.

Full Text PubMed - Russ CM, Tran T, Silverman M and Palfrey J. A study of global health elective outcomes: a pediatric residency experience. Glob Pediatr Health. 2017; 4: 2333794-23337916683806.

Full Text PubMed - Lu PM, Park EE, Rabin TL, Schwartz JI, Shearer LS, Siegler EL and Peck RN. Impact of global health electives on us medical residents: a systematic review. Ann Glob Health. 2018; 84: 692-703.

Full Text PubMed - Rees CA, Lukolyo H, Keating EM, Dearden KA, Luboga SA, Schutze GE and Kazembe PN. Authorship in paediatric research conducted in low- and middle-income countries: parity or parasitism? Trop Med Int Health. 2017; 22: 1362-1370.

Full Text PubMed - Abimbola S. The foreign gaze: authorship in academic global health. BMJ Glob Health. 2019; 4: 002068.

Full Text PubMed - Bolon I, Mason J, O'Keeffe P, Haeberli P, Adan HA, Karenzi JM, Osman AA, Thumbi SM, Chuchu V, Nyamai M, Babo Martins S, Wipf NC and Ruiz de Castañeda R. One Health education in Kakuma refugee camp (Kenya): from a MOOC to projects on real world challenges. One Health. 2020; 10: 100158.

Full Text PubMed - Bothara RK, Tafuna'i M, Wilkinson TJ, Desrosiers J, Jack S, Pattemore PK, Walls T, Sopoaga F, Murdoch DR and Miller AP. Global health classroom: mixed methods evaluation of an interinstitutional model for reciprocal global health learning among Samoan and New Zealand medical students. Global Health. 2021; 17: 99.

Full Text PubMed - Haynes N, Saint-Joy V and Swain J. Global health imperative to prioritizing cardiovascular education. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021; 77: 2749-2753.

Full Text PubMed - Hou L, Mehta SD, Christian E, Joyce B, Lesi O, Anorlu R, Akanmu AS, Imade G, Okeke E, Musah J, Wehbe F, Wei JJ, Gursel D, Klein K, Achenbach CJ, Doobay-Persaud A, Holl J, Maiga M, Traore C, Sagay A, Ogunsola F and Murphy R. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global health research training and education. J Glob Health. 2020; 10: 020366.

Full Text PubMed - Jacquet GA, Umoren RA, Hayward AS, Myers JG, Modi P, Dunlop SJ, Sarfaty S, Hauswald M and Tupesis JP. The Practitioner's Guide to Global Health: an interactive, online, open-access curriculum preparing medical learners for global health experiences. Med Educ Online. 2018; 23: 1503914.

Full Text PubMed - Kuriyan R, Griffiths JK, Finkelstein JL, Thomas T, Raj T, Bosch RJ, Kurpad AV and Duggan C. Innovations in nutrition education and global health: the Bangalore Boston nutrition collaborative. BMC Med Educ. 2014; 14: 5.

Full Text PubMed - Ziemba R, Sarkar NJ, Pickus B, Dallwig A, Wan JA and Alcindor H. Using international videoconferencing to extend the global reach of community health nursing education. Public Health Nurs. 2016; 33: 360-370.

Full Text PubMed - Gros P, Rotstein D, Kinach M, Chan DK, Montalban X, Freedman M and Sasikumar S. Innovation in resident education - description of the Neurology International Residents Videoconference and Exchange (NIRVE) program. J Neurol Sci. 2021; 420: 117222.

Full Text PubMed - Krohn KM, Sundberg MA, Quadri NS, Stauffer WM, Dhawan A, Pogemiller H, Tchonang Leuche V, Kesler S, Gebreslasse TH, Shaughnessy MK, Pritt B, Habib A, Scudder B, Sponsler S, Dunlop S and Hendel-Paterson B. Global health education during the COVID-19 pandemic: challenges, adaptations, and lessons learned. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021; 105: 1463-1467.

Full Text PubMed - Mirza A, Gang L and Chiu T. Utilizing virtual exchange to sustain global health partnerships in medical education. Ann Glob Health. 2021; 87: 24.

Full Text PubMed - Atkins S, Yan W, Meragia E, Mahomed H, Rosales-Klintz S, Skinner D and Zwarenstein M. Student experiences of participating in five collaborative blended learning courses in Africa and Asia: a survey. Glob Health Action. 2016; 9: 28145.

Full Text PubMed - Bensman RS, Slusher TM, Butteris SM, Pitt MB, On Behalf Of The Sugar Pearls Investigators , Becker A, Desai B, George A, Hagen S, Kiragu A, Johannsen R, Miller K, Rule A and Webber S. Creating online training for procedures in global health with PEARLS (Procedural Education for Adaptation to Resource-Limited Settings). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017; 97: 1285-1288.

Full Text PubMed - Bowen K, Barry M, Jowell A, Maddah D and Alami NH. Virtual exchange in global health: an innovative educational approach to foster socially responsible overseas collaboration. Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2021; 18: 32.

Full Text PubMed - Kiwanuka JK, Ttendo SS, Eromo E, Joseph SE, Duan ME, Haastrup AA, Baker K and Firth PG. Synchronous distance anesthesia education by Internet videoconference between Uganda and the United States. J Clin Anesth. 2015; 27: 499-503.

Full Text PubMed - Prosser M, Stephenson T, Mathur J, Enayati H, Kadie A, Abdi MM, Handuleh JIM and Keynejad RC. Reflective practice and transcultural psychiatry peer e-learning between Somaliland and the UK: a qualitative evaluation. BMC Med Educ. 2021; 21: 58.

Full Text PubMed - Samuels H, Rojas-Luengas V, Zereshkian A, Deng S, Moodie J, Veinot P, Bowry A and Law M. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the Global Medical Student Partnership program in undergraduate medical education. Can Med Educ J. 2020; 11: 90-98.

Full Text PubMed - Taekman JM, Foureman MF, Bulamba F, Steele M, Comstock E, Kintu A, Mauritz A and Olufolabi A. A novel multiplayer screen-based simulation experience for African learners improved confidence in management of postpartum hemorrhage. Front Public Health. 2017; 5: 248.

Full Text PubMed - Ezeonwu M, Berkowitz B and Vlasses FR. Using an academic-community partnership model and blended learning to advance community health nursing pedagogy. Public Health Nurs. 2014; 31: 272-280.

Full Text PubMed - Carrasco H, Fuentes P, Eguiluz I, Lucio-Ramírez C, Cárdenas S, Leyva Barrera IM and Pérez-Jiménez M. Evaluation of a multidisciplinary global health online course in Mexico. Glob Health Res Policy. 2020; 5: 48.

Full Text PubMed - Stallwood L, Adu PA, Tairyan K, Astle B and Yassi A. Applying equity-centered principles in an interprofessional global health course: a mixed methods study. BMC Med Educ. 2020; 20: 224.

Full Text PubMed - Addo-Atuah J, Dutta A and Kovera C. A global health elective course in a PharmD curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014; 78: 187.

Full Text PubMed - Amerson R. Preparing undergraduates for the global future of health care. Ann Glob Health. 2019; 85: 41.

Full Text PubMed - Chastonay P, Zesiger V, Moretti R, Cremaschini M, Bailey R, Wheeler E, Mattig T, Avocksouma DA and Mpinga EK. A public health e-learning master's programme with a focus on health workforce development targeting francophone Africa: the University of Geneva experience. Hum Resour Health. 2015; 13: 68.

Full Text PubMed - Falleiros de Mello D, Larcher Caliri MH, Villela Mamede F, Fernandes de Aguiar Tonetto EM and Resop Reilly J. An innovative exchange model for global and community health nursing education. Nurse Educ. 2018; 43: 1-4.

Full Text PubMed - Gruner D, Pottie K, Archibald D, Allison J, Sabourin V, Belcaid I, McCarthy A, Brindamour M, Augustincic Polec L and Duke P. Introducing global health into the undergraduate medical school curriculum using an e-learning program: a mixed method pilot study. BMC Med Educ. 2015; 15: 142.

Full Text PubMed - Hannigan NS, Takamiya K and Lerebours Nadal L. Sharing a Piece of the PIIE: Program of International Interprofessional Education/Programa Internacional Interprofesional Educativo. J Nurs Educ. 2015; 54: 716-718.

Full Text PubMed - Kulier R, Gülmezoglu AM, Zamora J, Plana MN, Carroli G, Cecatti JG, Germar MJ, Pisake L, Mittal S, Pattinson R, Wolomby-Molondo JJ, Bergh AM, May W, Souza JP, Koppenhoefer S and Khan KS. Effectiveness of a clinically integrated e-learning course in evidence-based medicine for reproductive health training: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012; 308: 2218-2225.

Full Text PubMed - Lee SJ, Park J, Lee YJ, Lee S, Kim WH and Yoon HB. The feasibility and satisfaction of an online global health education course at a single medical school: a retrospective study. Korean J Med Educ. 2020; 32: 307-315.

Full Text PubMed - Martini N, Caceres R. Triune Case Study: an exploration into inter-professional education (IPE) in an online environment supporting global health. International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education. 2012;20(3):68-86.

- Poirier TI, Devraj R, Blankson F and Xin H. Interprofessional online global health course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016; 80: 155.

Full Text PubMed - Ravi K, Nkuliza D, Patel R, Niyitegeka J, Davidson S and Aruparayil N. Fostering bidirectional trainee-led partnerships through a technology-assisted journal club - The GASOC experience. Trop Doct. 2022; 52: 139-141.

Full Text PubMed - Sarkar N, Dallwig A and Abbott P. Community health nursing through a global lens. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015; 209: 135-139.

PubMed - Sue GR, Covington WC and Chang J. The ReSurge global training program: a model for surgical training and capacity building in global reconstructive surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2018; 81: 250-256.

Full Text PubMed - Thorp M, Pool KL, Tymchuk C and Saab F. WhatsApp linking Lilongwe, Malawi to Los Angeles: impacting medical education and clinical management. Ann Glob Health. 2021; 87: 20.

Full Text PubMed - Ton TG, Gladding SP, Zunt JR, John C, Nerurkar VR, Moyer CA, Hobbs N, McCoy M and Kolars JC. The development and implementation of a competency-based curriculum for training in global health research. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015; 92: 163-171.

Full Text PubMed - Utley-Smith Q. An online education approach to population health in a global society. Public Health Nurs. 2017; 34: 388-394.

Full Text PubMed - Wu A, Noël GPJC, Wingate R, Kielstein H, Sakurai T, Viranta-Kovanen S, Chien CL, Traxler H, Waschke J, Vielmuth F, Sagoo MG, Kitahara S, Kato Y, Keay KA, Olsen J and Bernd P. An international partnership of 12 anatomy departments - improving global health through internationalization of medical education. Ann Glob Health. 2020; 86: 27.

Full Text PubMed