Measuring continuing medical education conference impact and attendee experience: a scoping review

Lisa Albrecht1, Misty Pratt2, Rhiannon Ng3, Jeremy Olivier1, Margaret Sampson1, Neal Fahey4, Jess Gibson5, Anna-Theresa Lobos6, Katie O'Hearn1, Dennis Newhook1, Stephanie Sutherland1 and Dayre McNally6

1Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada

2ICES, Toronto, Canada

3University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

4KPMG Canada, Quebec, Canada

5Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada

6Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Canada

Submitted: 06/03/2023; Accepted: 14/02/2024; Published: 29/02/2024

Int J Med Educ. 2024; 15:15-33; doi: 10.5116/ijme.65cc.8c88

© 2024 Lisa Albrecht et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use of work provided the original work is properly cited. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0

Abstract

Objectives: The aim was to comprehensively identify published research evaluating continuing medical education conferences, to search for validated tools and perform a content analysis to identify the relevant domains for conference evaluation.

Methods: We used scoping review methodology and searched MEDLINE® for relevant English or French literature published between 2008 and 2022 (last search June 3, 2022). Original research (including randomized controlled trials, non-randomized studies, cohort, mixed-methods, qualitative studies, and editorial pieces) where investigators described impact, experience, or motivations related to conference attendance were eligible. Citations were assessed in triplicate, and data extracted in duplicate.

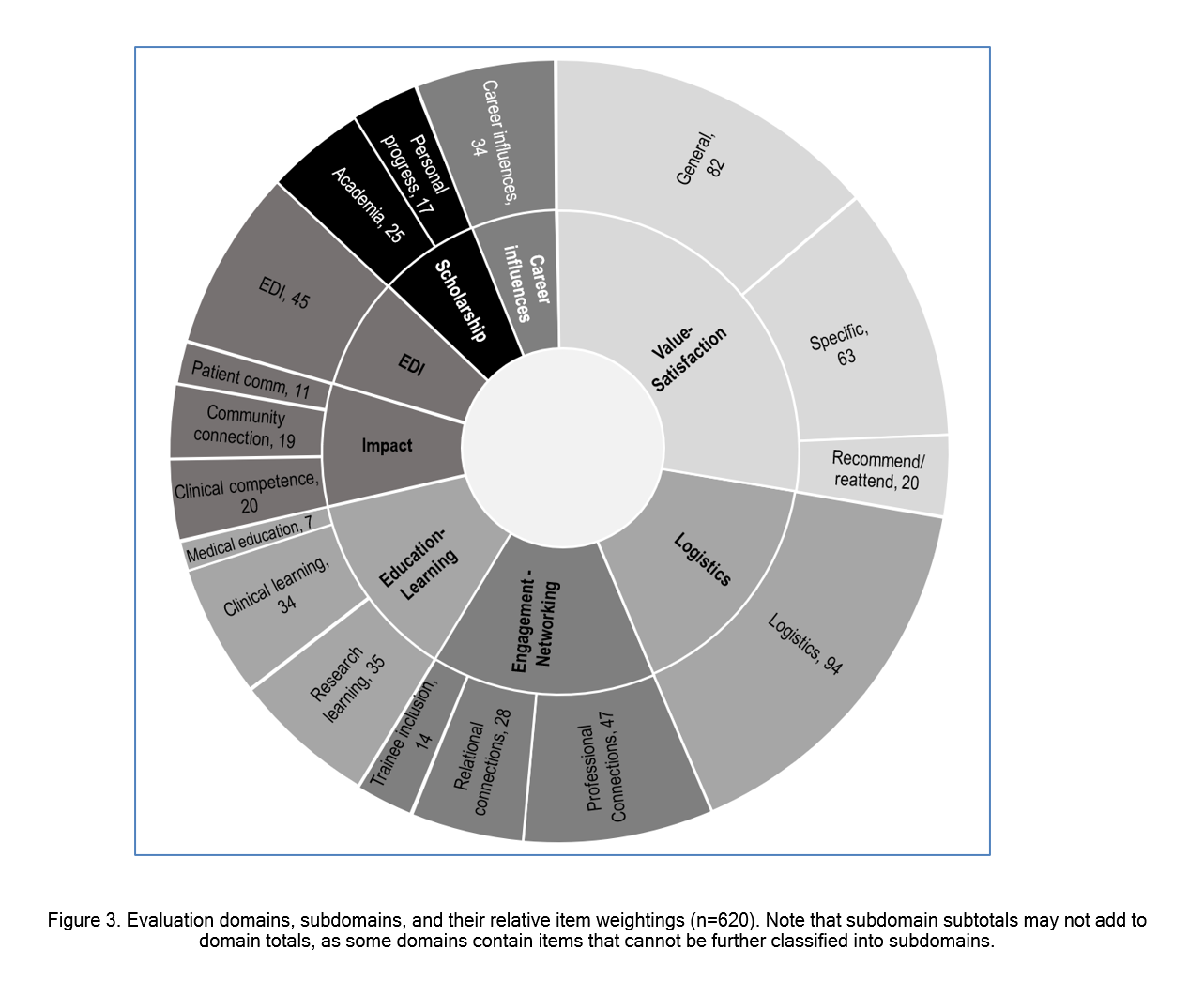

Results: Eighty-three studies were included, 69 (83%) of which were surveys or interview based, with the majority conducted at the end of or following conference conclusion. Of the 74 tools identified, only one was validated and was narrowly focused on a specific conference component. A total of 620 items were extracted and categorized into 4 a priori suggested domains (engagement-networking, education-learning, impact, scholarship), and an additional 4 identified through content analysis (value-satisfaction, logistics, equity-diversity-inclusivity, career influences). Time trends were evident, including the absence of items related to equity-diversity-inclusivity prior to 2019, and a focus on logistics, particularly technology and virtual conferences, since 2020.

Conclusions: This study identified 8 major domains relevant for continuing medical education conference evaluation. This work is of immediate value to individuals and organizations seeking to either design or evaluate a conference and represents a critical step in the development of a standardized tool for conference evaluation.

Introduction

Continuing medical education (CME) conferences are an integral part of health care. CME conferences are widely regarded as essential by clinicians, trainees, and the patients they serve as they support critical activities such as knowledge exchange, networking, and scholarly initiatives like research.1-4 The importance of CME conferences is further highlighted by their prominence in physician maintenance of certification4 and correlation between lack of opportunities to attend conferences and increased risk of burnout and feelings of inadequate knowledge or isolation.5 As an example, in a longitudinal study of emergency physicians opportunity to attend conferences was associated with a 3 times lower risk of burnout.5 Given the significance to health care and academia, there has been rapid growth and global expansion in the conference industry over the past century, with some estimates suggesting hundreds of thousands of events hosted globally each year.6-8 While this growth has benefits, it also presents significant downsides, including substantial time and financial investments (organizers and attendees) with increasingly recognized environmental consequences. A study of a single mid-sized American conference estimated that more than 10 000 tonnes of carbon dioxide were generated by air travel alone – equivalent to the annual amount produced by 550 US citizens.9 Moving forward, it is critical the field consider the costs and environmental impact of conferences, and strive to maximize value to attendees, patients, and the healthcare system.

Despite their importance and cost, there is no standardized means for conference evaluation, leading to several issues. First, with such a large number of conference options available within all specialities, attendees have no objective means of knowing which conferences provide the greatest value and/or best suit their individual needs. Available evidence suggests the approach to conference design and implementation can significantly influence impact. As an example, multiple studies show conferences that utilize both interactive and didactic seminars have more learning when compared to solely didactic or interactive seminars.1, 10-13 The lack of standardized evaluation tools makes it challenging for academic and industry researchers to demonstrate and quantify the value of new approaches, innovations and technologies. Consequently, conference organizers and their financers must make decisions about how to spend the limited resource (time and money) when designing their conference without access to this data.

To begin addressing the gap in high quality conference evaluation methodology, we sought to perform a scoping review of the published research evaluating CME conferences. Objective one was to comprehensively identify research studies evaluating conference experience, with the goal of identifying and examining the tools and frameworks utilized. Objective two was to compile a repository of frequently observed evaluation domains and subdomains based on information extracted from the studies. The findings of this scoping review will be of immediate use to individuals or organizations seeking to design or evaluate a conference and represents a critical first step in developing a standardized tool for conference evaluation.

Methods

We prepared a scoping review protocol guided by established methodology14 and published the protocol on Open Science Framework 04-May-2021. The project was completed at a tertiary care pediatric hospital associated with the University of Ottawa (Ottawa, Canada). Results are reported according to the PRISMA Scoping Review checklist (see supplemental digital appendix 1).

Literature search and study selection

Two information specialists co-developed the search strategy using Peer-Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) Checklist principles15 in consultation with the review team, after identification of seven eligible (true positive) articles used for key word generation. Following information specialist advice (M.S.), we conducted the search solely in MEDLINE as it has indexing designed specifically to identify citations specific to conferences/congress. In databases without such indexing, it is difficult to selectively retrieve research about conferences (rather than conferences about research) due to the limitations of Boolean logic (see supplemental digital appendix 2).

We uploaded RIS files and screened citations using insightScope, a web-platform designed to facilitate a large-team or crowdsourcing approach to citation screening.16 Each citation was assessed independently and in triplicate at both the title-abstract and full-text screening levels (M.P., N.F., R.N., J.G., K.O., J.O., L.A.), with conflicts resolved by team consensus. Prior to title and abstract screening, a test set of 50 citations randomly selected from the full set (enriched with 5 true positives) were screened by all study team members to identify discrepancies and clarify eligibility criteria.16

Inclusion criteria

We included English and French-language medical studies published from 2008 onward (last search conducted June 3, 2022). This date was chosen because the Medical Subject Heading term “Congresses as Topic” was introduced to the National Library of Medicine’s Resource Description Framework in the year 2008.17 We sought to identify studies representing original research where the investigators intended on evaluating, quantifying or describing impact, participant experience, or motivations for conference attendance. This included original research focused on the development or validation of an instrument (i.e., scale, score, instrument, survey, app) intended to evaluate conference impact or participant experience. A wide variety of study designs were eligible including randomized controlled trials, non-randomized studies, cohorts, mixed-methods, and qualitative studies.

Editorials, letters, commentaries, and opinion pieces were not eligible for inclusion unless the authors described the development of original research or creation of an evaluation tool or framework. Systematic reviews were to be retained to identify both potentially relevant studies from reference lists, and document conference outcomes of interest. To promote sensitivity, impact and experience were not rigidly defined, and screeners were encouraged to be inclusive. The populations of interest included conference organizers, attendees (health care professionals, trainees, and researchers), and other stakeholders (patients, caregivers, and policy makers). Studies were excluded if the conference was not related to health or medicine and if the format of the conference/congress was out of scope.

Data collection and quality assessment

See supplemental digital appendix 3 for the full list of variables in data extraction. Data extraction was performed independently and in duplicate (M.P., N.F., R.N., J.G., K.O., J.O., L.A.), with disagreements resolved initially through consensus and then through consultation with the study lead (D.M.). The data extraction tool was developed using an iterative process by which study team members (D.M., M.P., N.F., R.N., AT.L.) participated in three rounds of data extraction for a total of 15 citations. A key component of data extraction was recording the individual outcomes and/or questions comprising the evaluation tools (e.g., surveys) included in the studies. When the tool was not provided, these items were extracted from the text, tables or figures in the article. Conference characteristics (e.g., attendance, location, timing of evaluation tool administration) were also extracted from article text. When available, we extracted variables related to the design of the evaluation tools, including any mention of validation studies, pilot testing, or use of methodological frameworks. Given the scoping nature of the review and expectation of significant heterogeneity (population, methodology), we did not a priori plan either meta-analyses or a formal assessment of the methodologic quality of the articles using a standardized tool.18 However, a general assessment of study quality using relevant elements common to quality assessment tools was performed (supplementary digital appendix 5).

Analysis and statistics

Data related to study characteristics was reported descriptively using counts with percentages or measures of central tendency and variance (e.g., mean/median with SD/IQR). Results are presented descriptively in text, tables, and figures.

Content analysis was performed for domain and subdomain identification using deductive and inductive approaches19 (D.M., L.A., D.N., S.S.). For the deductive stage, we identified four a priori domains based on a preliminary literature review and team expertise: engagement/networking, education/learning, impact (patients and policy), and scholarship. During data extraction, two independent assessors identified items from each study, with each classified directly into one of the a priori domains, and the remaining items placed in an unassigned group. This approach was piloted on an initial set of 10 studies, and item extraction was then completed for the remaining studies by two independent assessors. The team inductively sorted unassigned items into four additional domains, and further content analysis was performed to organize items into subdomains where appropriate (see supplemental digital appendix 4 for additional details and example items in each category). All items were reviewed by study for identification of differences in item number, wording and classification, with conflicts resolved through consensus or involvement of another core team member. As this was a review, institutional ethical approval was not required.

Results

Search findings

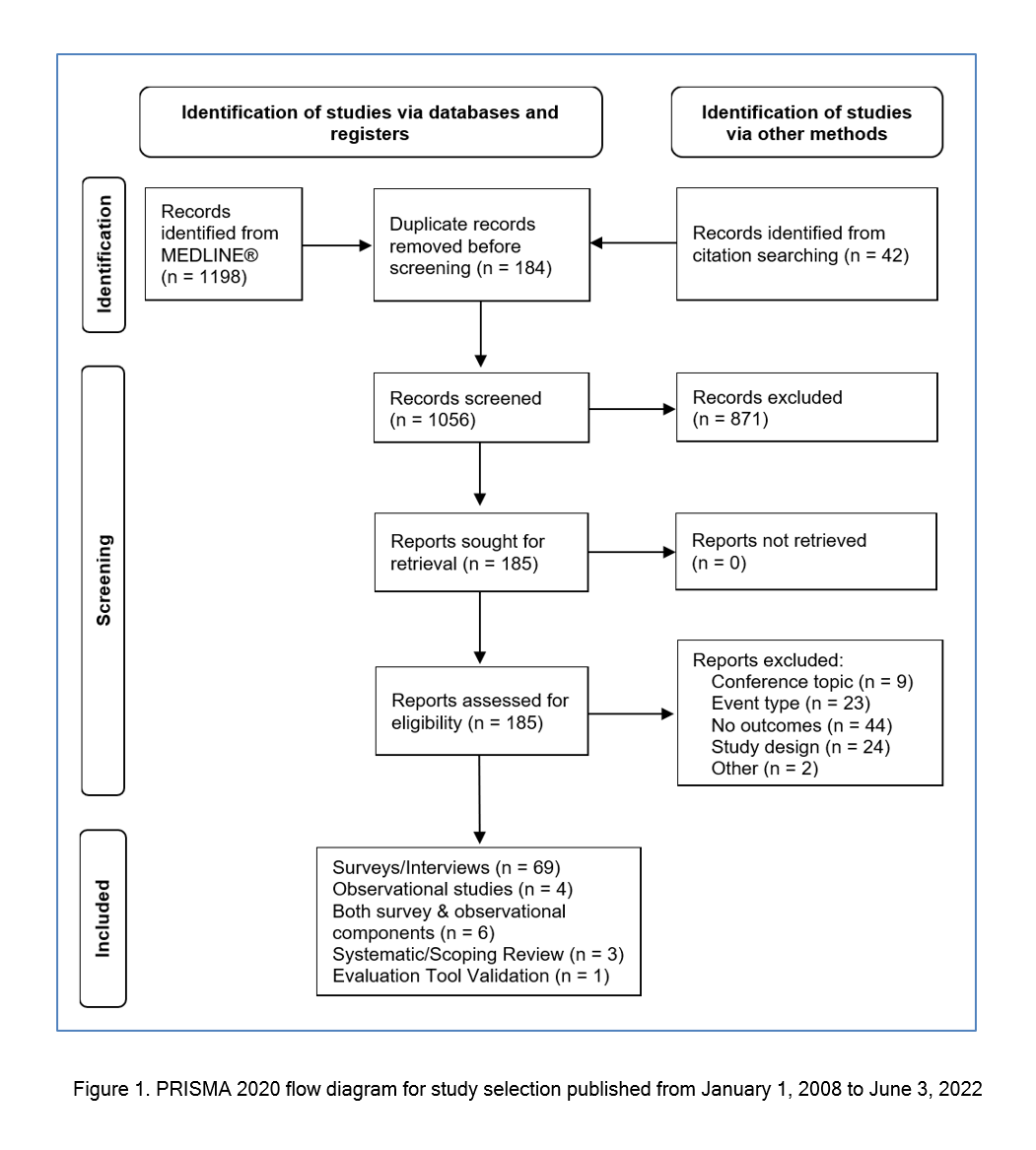

The original search and updates identified 1198 citations. An additional 42 potentially relevant citations not retrieved from the search of MEDLINE were identified during a review of the references lists of included studies. Following title and abstract screening, 185 studies were included for full text review. Of these, 83 were deemed eligible for analysis and included 69 surveys/interviews, 4 observational studies, 6 studies with both survey and observational components, 3 systematic/scoping reviews, and 1 tool validation study. The study screening process is summarized in the PRISMA 202020 flow diagram in Figure 1.

Conference study characteristics

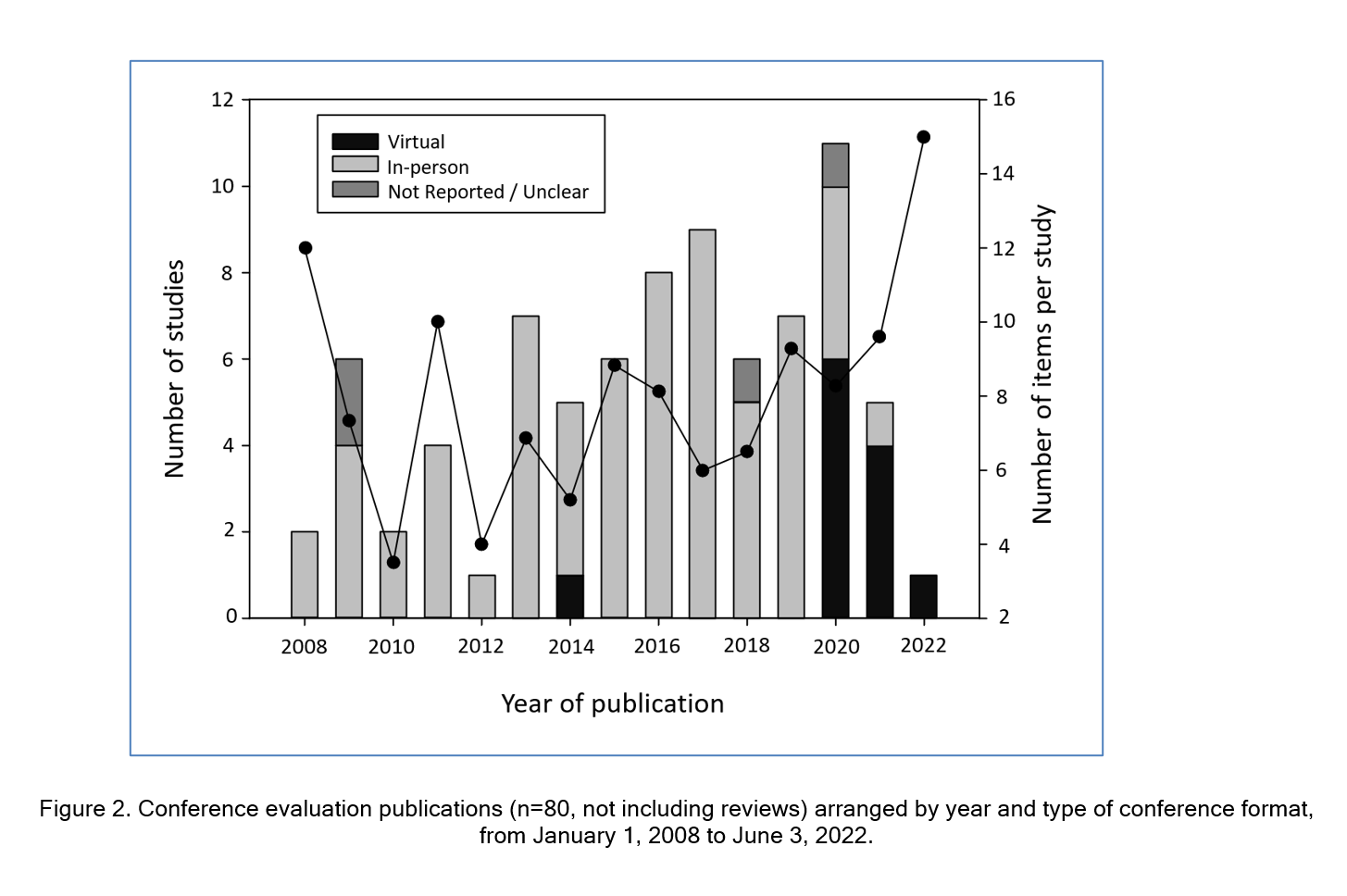

Geographically, the majority of the studies were based in North America (n=60, 72%), with Europe representing the second largest locale (n=10, 12%). Topics of the conferences being studied spanned 25 fields of health care and special interest groups with radiology (n=10, 12%), health policy (n=6, 7%), and a surgical discipline (n=6, 7%) being the most prevalent. Figure 2 provides the number of studies by year of publication and demonstrates a gradual rise in publications between 2008 and 2013, followed by a plateau, and a spike in 2020.

While the minority of studies from 2008-2019 assessed virtual conferences (n=1, 2%) or those for which attendance method wasn’t specified (n=6, 9%), there was a clear shift from 2020 onwards with 11 (65%) studies assessing conferences hosted virtually. Additional characteristics of the 83 studies 1, 3, 21-101 are summarized in Table 1. Our assessment of study quality indicators demonstrated certain elements such as clarity of study objective(s) and design were well detailed in most publications (≥90%). However, other indicators such as approach to tool development (23%), adequate outcome description (30%) and participant response rates (57%) were often lacking (full details in supplementary digital appendix 5).

Characteristics of conference evaluation methodology

Of the 83 studies, 74 (89%) used evaluation tools that sought direct input (via surveys or interviews) from the conference attendees. The remaining 9 (11%) studies included systematic and scoping reviews, discussion based/open-forum reflections on the conference, and observational trials linking conference attendance to other metrics (example: exam performance).

Among the 69 (83%) studies providing data on study respondent number, the median was 99 (IQR: 50-220). While most studies (n=56, 68%) included trainees in their conference evaluation, relatively few considered patients and/or caregivers (n=7, 8%). The majority of studies performed evaluations either immediately at the end of the conference (n=23, 28%) and/or post-conference conclusion (n=45, 54%). The length of follow-up for the studies that measured post-conference evaluation was reported in 21 (25%) studies and ranged from 2 days to 5 years. Additionally, there were 22 (26%) studies that gathered data from conference participants before or at the onset of the conference and again at or post-conference conclusion. Table 1 provides additional details on the approach to conference evaluation and participant recruitment.

Evaluation of tool quality and design

Of the 74 (89%) studies using surveys or interviews, 39 (53% of these studies) provided all or a portion of the tool. Of these, only one97 described their tool as having been validated and focused on participants’ attitudes related to a mobile device app intended for conference use. A second study reported using a partially validated tool,77 and specifically focused on how the conference impacted self-assessment of comfort with providing end of life care. For the remaining studies,13 (18% of those using surveys/interviews) described using an evaluation framework to inform their study, including tool development,3,22,29,38,41,49,55,64,68,69,74,83 of which 322,64,69 referenced the same primary source70 – a scoping review whose goal was to develop a conference evaluation framework. Of the remaining 24 (32% of those using surveys/interviews), only two studies reported performing any pilot testing of their tool,42,54 with an additional three29, 72, 80 suggesting the work itself represented a pilot study for tool assessment.

Content analysis: domains and subdomain identification

There were 620 individual items (evaluation questions or results obtained from surveys, interviews, and reported outcomes) identified and extracted from the studies, with a median of 6 items (IQR: 4-9) per study. As shown in Figure 2, there was a relatively stable average (median) number of items per study up to 2018, with the suggestion of a gradual increase from 2019 to 2022. Following content analysis, 8 major domains were identified (Figure 3), with the four a priori identified domains capturing only a minority of items (282, 45%). The four new domains identified during content analysis (value-satisfaction, logistics, equity-diversity-inclusivity (EDI), career influences) captured the majority of items (338, 55%). Further item analysis identified subdomains within 5 of the domains, including all 4 of the a priori domains and value-satisfaction. Supplementary digital appendix 4 provides a more detailed description of the findings from content analysis including one ore more example item from each domain/subdomain. While no subdomains were identified for the logistics domain, analysis did recognize that the large number of items (n=94) evaluated a heterogenous group of characteristics such as location, timing, and various aspects of content delivery and organization, including a more recent focus on whether technology facilitated or hindered the delivery of other domains (e.g. education, networking). Consistent with the more recent focus on technology, 10 study tools (published 2020 or later) contained items specifically related to COVID-19 and ease of transition to virtual conferences, preferences for methods of information exchange, and/or success of social media promotion of the conference. Similarly, a clear time trend was evident for the EDI domain, with the 45 items all originating from 9 studies published in 2019 or later. The final and least featured domain was career influences which included items primarily related to whether the conference improved participants’ understanding of careers in an area, and/or increased motivation to pursue careers, professional development, or further training in the field. Thirty-one of the 34 items (91%) originated from studies evaluating conferences where students/trainees were included in the eligible population, with 27 (79%) being conferences held specifically for students/trainees.

Discussion

This scoping review explored the published literature on CME conference evaluation with the goals of identifying validated instruments and relevant evaluation domains through content analysis. This work identified 83 studies originating from a range of medical fields, but no broadly applicable validated tools. While inspection of individual studies demonstrated that only a small minority described following recommended methodology for survey development (for instance, pilot testing), the extraction and analysis of over 600 individual items allowed for the identification of several domains and subdomains directly useful to future research in this area.

As expected, conference evaluation research was confirmed to be of widespread interest, spanning over two dozen medical fields and originating worldwide. While interest was widespread, the field of radiology and diagnostic imaging produced three times as many publications (n=10) as the average in all other fields (n=3). The higher volume may be linked to interventional radiology’s (IR) recent recognition as a primary specialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties in 2012 and need to recruit trainees into dedicated IR residencies.59 This is consistent with the observation that all 10 of the radiology studies reported on conferences specifically held for trainees, with several tracking conference attendance over time and student attraction to the program.

Analyzing study location identified that the majority of studies (72%) originated from North America. This proportion may be explained in part by study methodology factors (decision to only included English and French articles) or regional/cultural differences in approach to scholarship/publication or continuing medical education (CME); CME and professional development are highly regulated within Canada, the United States, and most Western European and Australasian countries, but vary more globally in terms of policies, infrastructure, and enforcement.2, 102-104 Additionally, the reality of ‘conference inequity’ – where most global health conferences (and therefore evaluations on these) are held in higher income countries105 – is also borne out here, as only 16% of studies came from outside of North America and Europe. While the publication rate appeared to plateau or only minimally grow between 2014-2019, at an average of seven per year, a spike was observed in 2020 to 11 publications. This spike timed with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and as shown in Figure 2, these studies focused on assessing the impact of the necessary transition from in-person to virtual conferences. Although not implemented on a global scale prior to COVID-19, virtual conferences and webinars have been an important component of medical education prior to COVID-19 with proven success in knowledge transfer.

For instance, studies have shown improved standardized test scores following virtual lectures provided by first-world academic institutions to smaller hospitals in developing countries.106,107 While investigating the specific impact of virtual conferences is outside the scope of this research, seven of the 12 publications that evaluated virtual conferences reported attendee assessment as positive (i.e., the majority of participants reported equivalent or higher preference for the virtual format).60,61, 68, 71, 79, 81, 94 This was attributed to improved attendance, greater accessibility, and decreased environmental impact. Of the remaining publications, 3 of 12 did not specifically ask the participants about format preference, although respondents indicated that they had enjoyed the conference and were willing to continue meeting virtually;42, 89,96 1 of 12 reported a majority preference for in-person meetings;44 and the final study reported approximately equal preference for in-person and hybrid/virtual.82

Some studies attempted to evaluate conference impact using objective metrics – such as examining links between attendance and performance on the American Board of Emergency Medicine In-Training Examination and U.S. Medical Licensing Examination,39 or distributing case study questionnaires to conference participants and non-participants to determine “whether the diagnostic and therapeutic choices of program participants were consistent with evidence-based guidelines”.36 Of the studies that used surveys, only one97 described using validation processes such as iterative revisions, factor analysis, and Cronbach’s alpha methods to assess internal consistency.108,109 While of clear value, this tool may have limited general applicability as it was specifically designed to measure a mobile device app’s impact on conference experience. In the absence of validated tools, some of the studies (n=13) sought out and described the consideration of previously published conference evaluation frameworks as part of tool development. Finally, only two studies42, 54 mentioned performing any tool refinement or pilot testing prior to implementation, widely considered essential steps in survey development.110,111 Despite the inability to formally assess the quality of each instrument included in our review, the lack of validity evidence supporting these instruments raises concerns about their methodological quality, as do other aspects of our general quality assessment (such as response rate reporting and clear sample population descriptors).

Our content analysis identified eight major evaluation domains. The traditional conference format is geared toward bringing individuals together, usually physically, for the purpose of shared learning – so the observed heavy weighting in these domains as well as in satisfaction and logistics supports the assumption that evaluation weighting parallels conference goals. This format often leads to new mentorship and professional development opportunities for those who attend, and there are well-documented challenges for those who do not or cannot attend.105,112-115 The four domains identified inductively addressed value-satisfaction, logistics, EDI, and career influences. Items assessing logistics and EDI were primarily found in more recent publications. More recent studies also tended to highlight concerns surrounding in-person conferences, such as the environmental impacts and attendance inequity. Both the identified studies and broader literature suggest factors like funding, inability to travel to conference location, limited speaking opportunities/representation, family/clinical commitments, and intrinsic feelings of belonging as barriers that disproportionately affect in-person conference attendance of women, minorities, and residents of lower income countries.32,47,98,105,116-118 Items addressing conference environmental impact and gender-related conference inequity were primarily found in studies42,98 published after 2019, indicating these to be emerging priorities within the scientific community. Virtual conferences have the potential to reduce environmental impacts and provide more equitable and convenient opportunities for networking, learning, and collaboration to all attendees.

Patients and caregivers are another group for whom inclusion has been a growing priority and seven studies within this review specifically included these individuals as stakeholders, potentially reflecting the growing importance their inclusion in conference planning and implementation has on preventing discrepancies between patient and health professional priorities.38,41,63,69 Patient and caregiver conference participation avenues varied, ranging from being the primary audience for improved education and involvement in medical and scientific discussions,63,101 to inclusion as planners and speakers to better incorporate their feedback into research, health care, and policy.38,41 This trend reflects a similar shift in broader health care and research toward patient inclusion.119-121 While this is demonstrably valuable and multiple organizations (e.g., Stanford Medicine X, Patients Included, European Patients Forum) have created charters for ideal methods of inclusion in conferences, further discussion within the medical community of how to meaningfully incorporate patients and caregivers from an EDI standpoint is warranted. The Stanford Framework for Patient Partnership, which was written to guide patient inclusion in CME conferences and “could also be used by prospective delegates to evaluate conferences they are contemplating attending,”119 suggests that accommodation, co-design, engagement, and education and mentorship should be guiding principles in meaningful inclusion.

This scoping review has strengths and limitations to be considered. One major strength is our application of a widely-accepted methodological framework14,122 for conducting scoping reviews. Through this approach we were able to thoroughly capture trends in CME conference evaluation research including the recent emergence of EDI, environmental concerns, logistics and patient/caregivers as important considerations. One major study limitation was our search restriction to MEDLINE®, deemed necessary given the absence of terms related to congress or conferences in other relevant databases. As recommended for difficult-to-search topics (in this case by the research topic and feasibility of a primary database search123), we used ancillary search methods and, in particular, citation searching.124 While limiting to a single electronic database may have reduced the number of eligible studies included we anticipate it to be without major effect as only 5 additional eligible citations were identified through citation searching that were not in our original MEDLINE® search, and these were conference abstracts, yielding little reliable evidence. A second potential limitation was the inclusion of only English and French articles, which may have reduced the number of conference evaluation studies outside of North American and Europe, and potentially limit generalizability to other regions and cultures.

Conclusions

Through this scoping review we were able to map the published conference evaluation literature across many medical fields. This review did not identify a validated tool intended for conference evaluation, which suggests that organizers and research teams are developing their own instruments. While formal quality assessment was not performed, general quality assessment indicated that while study methodology was strong, tool development and recruitment techniques/reporting were weaker. This work confirmed the use of longstanding evaluation domains (e.g., education, networking) and revealed newer domains (e.g., EDI, found in studies published in 2019 or later) used in conference evaluations. The identification of domains, subdomains, and their relative weight may be useful to researchers seeking to evaluate future conferences, and to conference organizers to inform objectives, activities, and select indicators of success and impact. Additionally, by identifying widely-used domains (and subdomains) as well as trends in in-person vs virtual conference format, and by creating a database of sample items, this work helps set the stage for future projects aimed at developing more standardized evaluation instruments which can ultimately improve conference quality.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Lindsey Sikora, Head of Research Support (Health Sciences, Medicine, STEM) at the University of Ottawa, Ottawa ON for co-development of the search strategy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary file 1

Appendix 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist18 (S1.pdf, 61 kb)Supplementary file 2

Appendix 2. MEDLINE® search strategy (S2.pdf, 41 kb)Supplementary file 3

Appendix 3. Variables extracted from studies in scoping review (insightScope instrument) (S3.pdf, 81 kb)References

- Forsetlund L, Bjørndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O'Brien MA, Wolf F, Davis D, Odgaard-Jensen J and Oxman AD. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; 2009: 003030.

Full Text PubMed - Ali SA, Hamiz Ul Fawwad S, Ahmed G, Naz S, Waqar SA and Hareem A. Continuing Medical Education: A Cross Sectional Study on a Developing Country's Perspective. Sci Eng Ethics. 2018; 24: 251-260.

Full Text PubMed - Gopalan C, Halpin PA and Johnson KMS. Benefits and logistics of nonpresenting undergraduate students attending a professional scientific meeting. Adv Physiol Educ. 2018; 42: 68-74.

Full Text PubMed - Holmboe ES and Cassel C. Continuing medical education and maintenance of certification: essential links. Perm J. 2007; 11: 71-75.

Full Text PubMed - Cydulka RK and Korte R. Career satisfaction in emergency medicine: the ABEM Longitudinal Study of Emergency Physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2008; 51: 714-722.

Full Text PubMed - Klemeš JJ. Scientific conferences: organisation, participation and their future. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy. 2016; 18: 347-349.

Full Text - Fuchs E. Educational sciences, morality and politics: international educational congresses in the early twentieth century. Paedagogica Historica. 2004; 40: 757-784.

Full Text - Ioannidis JP. Are medical conferences useful? And for whom? JAMA. 2012; 307: 1257-1258.

Full Text PubMed - Callister ME and Griffiths MJ. The carbon footprint of the American Thoracic Society meeting. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007; 175: 417.

Full Text PubMed - Davis D, O'Brien MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P and Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999; 282: 867-874.

Full Text PubMed - Bloom BS. Effects of continuing medical education on improving physician clinical care and patient health: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005; 21: 380-385.

Full Text PubMed - Khan KS and Coomarasamy A. A hierarchy of effective teaching and learning to acquire competence in evidenced-based medicine. BMC Med Educ. 2006; 6: 59.

Full Text PubMed - Weller J and Harrison M. Continuing education and New Zealand anaesthetists: an analysis of current practice and future needs. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2004; 32: 59-63.

Full Text PubMed - Levac D, Colquhoun H and O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010; 5: 69.

Full Text PubMed - McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V and Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016; 75: 40-46.

Full Text PubMed - Nama N, Sampson M, Barrowman N, Sandarage R, Menon K, Macartney G, Murto K, Vaccani JP, Katz S, Zemek R, Nasr A and McNally JD. Crowdsourcing the Citation Screening Process for Systematic Reviews: Validation Study. J Med Internet Res. 2019; 21: 12953.

Full Text PubMed - U.S. National Library of Medicine. Medical subject headings RDF: congresses as topic [Internet]. [Cited 23 Oct 2023]; Available from: https://id.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/D003226.html.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö and Straus SE. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 169: 467-473.

Full Text PubMed - Hsieh HF and Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005; 15: 1277-1288.

Full Text PubMed - Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P and McKenzie JE. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021; 372: 160.

Full Text PubMed - Adelman RD, Ansell P, Breckman R, Snow CE, Ehrlich AR, Greene MG, Greenberg DF, Raik BL, Raymond JJ, Clabby JF, Fields SD and Breznay JB. Building psychosocial programming in geriatrics fellowships: a consortium model. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2011; 32: 309-320.

Full Text PubMed - Arellano DE, Goodman DA, Howlette T, Kroelinger CD, Law M, Phillips D, Jones J, Brantley MD and Fitzgerald M. Evaluation of the 2012 18th Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Epidemiology and 22nd CityMatCH MCH Urban Leadership Conference: six month impact on science, program, and policy. Matern Child Health J. 2014; 18: 1565-1571.

Full Text PubMed - Balesh E, Misono A, Attaya H, Wehrenberg-Klee E, Rao S, Specht K, Bonk S, Loomis S, Sheridan R, Mueller P and Walker T. Medical student perceptions of interventional radiology (IR): impact of an IR symposium. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016; 27: S234.

Full Text - Balon R, Guerra E, Meador-Woodruff JH, Oquendo MA, Salloum IM, Casiano DE and Nemeroff CB. Innovative approach to research training: research colloquium for junior investigators. Acad Psychiatry. 2011; 35: 11-14.

Full Text PubMed - Barrios-Anderson A, Liu DD, Snead J, Wu E, Lee DJ, Robbins J, Aguirre J, Tang O, Garcia CM, Pucci F, Anderson MN, Syed S, Shaaya E and Gokaslan ZL. The National Student Neurosurgical Research Conference: A Research Conference for Medical Students. World Neurosurg. 2021; 146: 398-404.

Full Text PubMed - Bartlett JA, Cao S, Mmbaga B, Qian X, Merson M and Kramer R. Partnership Conference. Ann Glob Health. 2017; 83: 630-636.

Full Text PubMed - Besterman AD, Williams JK, Reus VI, Pato MT, Voglmaier SM and Mathews CA. The Role of Regional Conferences in Research Resident Career Development: The California Psychiatry Research Resident Retreat. Acad Psychiatry. 2017; 41: 272-277.

Full Text PubMed - Brady R, McMenomy B, Chauhan A, Siebert D, Smith K and Eckmann DR. Introducing first-year radiology residents to the ACR at the AMCLC from 2009-2011: the potential impact for ACR and state radiological society memberships. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013; 10: 373-375.

Full Text PubMed - Brailo V, McKnight P, Kerr AR, Lodi G and Lockhart PB. World Workshop on Oral Medicine VII: What participants perceive as important. Oral Dis. 2019; 8-11.

Full Text PubMed - Brimmer DJ, McCleary KK, Lupton TA, Faryna KM and Reeves WC. Continuing medical education challenges in chronic fatigue syndrome. BMC Med Educ. 2009; 9: 70.

Full Text PubMed - Buethe J, Farrell J, Partovi S, Bochnakova T, Robbin M, McDaniel J, Kang P, Kapoor B, Tavri S and Patel I. Medical student (MS) interventional radiology (IR) symposium: raising awareness and interest in pursuing IR residency. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017; 28: S186.

Full Text - Casad BJ, Chang AL and Pribbenow CM. The Benefits of Attending the Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minority Students (ABRCMS): The Role of Research Confidence. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016; 15: .

Full Text PubMed - Cazzaniga S, Scerri L, Gabbud JP, Arenberger P, Borradori L and Naldi L. Factors influencing sessions' and speakers' evaluation: an analysis of seven consecutive European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology congress editions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018; 32: 2307-2313.

Full Text PubMed - Chen F, Cho W, Kim HJ and Levine DB. Trends in Attendance at Scoliosis Research Society Annual Meetings (SRS AM) and International Meeting on Advanced Spine Techniques (IMAST): Location, Location, Location. Spine Deform. 2017; 5: 238-243.

Full Text PubMed - de Camargo CRS, Schoueri JHM, Neto FL, Segalla PB, Del Giglio A and Cubero DIG. Medical Student Oncology Congress: Designed and Implemented by Brazilian Medical Students. J Cancer Educ. 2018; 33: 1151-1158.

Full Text PubMed - Drexel C, Merlo K, Basile JN, Watkins B, Whitfield B, Katz JM, Pine B and Sullivan T. Highly interactive multi-session programs impact physician behavior on hypertension management: outcomes of a new CME model. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011; 13: 97-9105.

Full Text PubMed - Foster J, Guisinger V, Graham A, Hutchcraft L and Salmon M. Global Government Health Partners' Forum 2006: eighteen months later. Int Nurs Rev. 2010; 57: 173-179.

Full Text PubMed - Gainforth HL, Baxter K, Baron J, Michalovic E, Caron JG and Sweet SN. RE-AIMing conferences: evaluating the adoption, implementation and maintenance of the Rick Hansen Institute's Praxis 2016. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019; 17: 39.

Full Text PubMed - Gene Hern H, Wills C, Alter H, Bowman SH, Katz E, Shayne P and Vahidnia F. Conference attendance does not correlate with emergency medicine residency in-training examination scores. Acad Emerg Med. 2009; 63-66.

Full Text PubMed - Gosselin-Tardif A, Butler-Laporte G, Vassiliou M, Khwaja K, Ntakiyiruta G, Kyamanywa P, Razek T and Deckelbaum DL. Enhancing medical students' education and careers in global surgery. Can J Surg. 2014; 57: 224-225.

Full Text PubMed - Gutman T, Manera KE, Baumgart A, Johnson DW, Wilkie M, Boudville N, Craig JC, Dong J, Jesudason S, Mehrotra R, Neu A, Shen JI, Van Biesen W, Blake PG, Brunier G, Cho Y, Jefferson N, Lenga I, Mann N, Mendelson AA, Perl J, Sanabria RM, Scholes-Roberston N, Schwartz D, Teitelbaum I and Tong A. "Can I go to Glasgow?" Learnings from patient involvement at the 17th Congress of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD). Perit Dial Int. 2020; 40: 12-25.

Full Text PubMed - Haage V. A survey of travel behaviour among scientists in Germany and the potential for change. Elife. 2020; 9: .

Full Text PubMed - Hanrahan J, Burford C, Ansaripour A, Smith B, Sysum K, Rajwani KM, Huett M and Zebian B. Undergraduate neurosurgical conferences - what role do they play? Br J Neurosurg. 2019; 33: 76-78.

Full Text PubMed - Holder BM, Tolan SE, Heinrich KK, Miller KC, Hudson N, Nehra G, Pizzo ME, Storck SE, Elmquist WF, Engelhardt B, Loryan I, Toborek M, Bauer B, Hartz AMS and Kim BJ. Brain barriers virtual: an interim solution or future opportunity? Fluids Barriers CNS. 2022; 19: 19.

Full Text PubMed - Husmann PR, O'Loughlin VD and Brokaw JJ. Knowledge Gains and Changing Attitudes from the Anatomy Education Research Institute (AERI 2017): A Mixed Methods Analysis. Anat Sci Educ. 2020; 13: 192-205.

Full Text PubMed - Ilic D and Rowe N. What is the evidence that poster presentations are effective in promoting knowledge transfer? A state of the art review. Health Info Libr J. 2013; 30: 4-12.

Full Text PubMed - Interian A and Escobar JI. The use of a mentoring-based conference as a research career stimulation strategy. Acad Med. 2009; 84: 1389-1394.

Full Text PubMed - Jaffe DM, Knapp JF and Jeffe DB. Outcomes evaluation of the 2005 National Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellows' Conference. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008; 24: 255-261.

Full Text PubMed - Jaffe DM, Knapp JF and Jeffe DB. Final evaluation of the 2005 to 2007 National Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellows' Conferences. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009; 25: 295-300.

Full Text PubMed - James JB, Gunn AL and Akob DM. Binning Singletons: Mentoring through Networking at ASM Microbe 2019. mSphere. 2020; 5: .

Full Text PubMed - Kates AM, Morris P, Poppas A and Kuvin JT. Impact of Live, Scientific Annual Meetings in Today's Cardiovascular World. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72: 2082-2085.

Full Text PubMed - Kattapuram TM, Sheth RA, Ganguli S, Mueller PR and Walker TG. Interventional Radiology Symposium for Medical Students: Raising Awareness, Understanding, and Interest. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015; 12: 968-971.

Full Text PubMed - Kiramijyan S, Didier R, Koifman E and Negi SI. What should a fellow-in-training expect at national cardiovascular conferences? The interventional cardiology fellows' perspective. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016; 17: 438-440.

Full Text PubMed - LaSalle EE, Fitzgibbons SC and Chahine AA. E-Mailed Conference Synopses as a Tool for Resident and Faculty Development. J Surg Educ. 2018; 75: 861-869.

Full Text PubMed - Le TT and Montandon SV. Efficacy of American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology symposia and workshops. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013; 111: 69-70.

Full Text PubMed - Leung CP, Klausner AP, Habibi JR, King AB and Feldman A. Audience response system: a new learning tool for urologic conferences. Can J Urol. 2013; 20: 7042-7045.

PubMed - Lin JA, Hsu AT, Huang JJ, Daniel BW, Lee CH, Kwon SH, Tang ET, Chu CF, Chien CT, Chuang DC, Lu JC, Koshima I, Wang ZT, Hao L, Chen C and Chang TN. Impact of Social Media on Current Medical Conferences. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2019; 35: 452-461.

Full Text PubMed - Macerollo A, Róna-Vörös K, Holler N, Chiperi R, Györfi O, Papp V, Sauerbier A, Balicza P and Sellner J. Preferences of residents and junior neurologists to attend conferences--an EAYNT survey. J Neurol Sci. 2015; 357: 297-299.

Full Text PubMed - Makary MS, Rajan A, Miller RJ, Elliott ED, Spain JW and Guy GE. Institutional Interventional Radiology Symposium Increases Medical Student Interest and Identifies Target Recruitment Candidates. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2019; 48: 363-367.

Full Text PubMed - Martin-Gorgojo A, Bernabeu-Wittel J, Linares-Barrios M, Russo-de la Torre F, Garcia-Doval I and del Rio-de la Torre E. Attendee Survey and Practical Appraisal of a Telegram®-Based Dermatology Congress During the COVID-19 Confinement. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas (Engl Ed). 2020; 111: 852-860.

Full Text - McDowell L, Goode S and Sundaresan P. Adapting to a global pandemic through live virtual delivery of a cancer collaborative trial group conference: The TROG 2020 experience. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2020; 64: 414-421.

Full Text PubMed - McMenomy B, Zingula S, Smith K and Hunter D. Introducing first-year radiology residents to the ACR at the AMCLC: the effect on future ACR and state radiologic society membership and participation. J Am Coll Radiol. 2010; 7: 339-345.

Full Text PubMed - Mendel P, Ngo VK, Dixon E, Stockdale S, Jones F, Chung B, Jones A, Masongsong Z and Khodyakov D. Partnered evaluation of a community engagement intervention: use of a kickoff conference in a randomized trial for depression care improvement in underserved communities. Ethn Dis. 2011; 21: 1-78.

PubMed - Milko E, Wu D, Neves J, Neubecker AW, Lavis J and Ranson MK. Second Global Symposium on Health Systems Research: a conference impact evaluation. Health Policy Plan. 2015; 30: 612-623.

Full Text PubMed - Misono A, Wehrenberg-Klee E, Rao S, Fadl S, Attaya H, Bonk S, Sheridan R, Loomis S, Mueller P and Walker T. Medical student IR symposia: characterizing impact on medical student career choices. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017; 28: S189.

Full Text - Morrato EH, Rabin B, Proctor J, Cicutto LC, Battaglia CT, Lambert-Kerzner A, Leeman-Castillo B, Prahl-Wretling M, Nuechterlein B, Glasgow RE and Kempe A. Bringing it home: expanding the local reach of dissemination and implementation training via a university-based workshop. Implement Sci. 2015; 10: 94.

Full Text PubMed - Nebrig D, Munafo J, Goddard J and Tierney C. The Conference Facilitator Model: Improving the Value of Conference Attendance for Attendees and the Organization. J Nurs Adm. 2015; 45: 443-448.

Full Text PubMed - Nelson BA, Lapen K, Schultz O, Nangachiveettil J, Braunstein SE, Fernandez C, Fields EC, Gunther JR, Jeans E, Jimenez RB, Kharofa JR, Laucis A, Yechieli RL, Gillespie EF and Golden DW. The Radiation Oncology Education Collaborative Study Group 2020 Spring Symposium: Is Virtual the New Reality? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021; 110: 315-321.

Full Text PubMed - Neves J, Lavis JN, Panisset U and Klint MH. Evaluation of the international forum on evidence informed health policymaking: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia - 27 to 31 August 2012. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014; 12: 14.

Full Text PubMed - Neves J, Lavis JN and Ranson MK. A scoping review about conference objectives and evaluative practices: how do we get more out of them? Health Res Policy Syst. 2012; 10: 26.

Full Text PubMed - Newman TH, Robb H, Michaels J, Farrell SM, Kadhum M, Vig S and Green JSA. The end of conferences as we know them? Trainee perspectives from the Virtual ACCESS Conference 2020. BJU Int. 2021; 127: 263-265.

Full Text PubMed - Nichols NL, Ilatovskaya DV and Matyas ML. Monitoring undergraduate student needs and activities at Experimental Biology: APS pilot survey. Adv Physiol Educ. 2017; 41: 186-193.

Full Text PubMed - Normore R, Greene H, DeLong A and Furey A. The Orthopedic Trauma Symposium: improving care of orthopedic injuries in Haiti. Can J Surg. 2017; 60: 228-235.

Full Text PubMed - O'Loughlin VD, Husmann PR and Brokaw JJ. Development and Implementation of the Inaugural Anatomy Education Research Institute (AERI 2017). Anat Sci Educ. 2019; 12: 181-190.

Full Text PubMed - Paige JT, Farrell TM, Bergman S, Selim N, Harzman AE, Schwarz E, Hori Y, Levine J and Scott DJ. Evolution of practice gaps in gastrointestinal and endoscopic surgery: 2012 report from the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) Continuing Education Committee. Surg Endosc. 2013; 27: 4429-4438.

Full Text PubMed - Patel M, Mehta A, Ahmed O and Navuluri R. The Midwest Interventional Radiology Medical Student Symposium: a model for the future of IR medical student education and recruitment. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016; 27: S229-S230.

Full Text - Price DM, Wyse DM, Conrad CM, Harden KL, Montagnini M and Ghosh B. Creating a Sustainable Palliative Care Education Conference for Healthcare Professionals. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2020; 36: 82-87.

Full Text PubMed - Rashid S, Kaufman C, Rashid S and Ayyagari R. Increasing medical student awareness and interest in IR via a 1-day symposium. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016; 27: S78-S79.

Full Text - Rose C, Mott S, Alvarez A and Lin M. Physically distant, educationally connected: Interactive conferencing in the era of COVID-19. Med Educ. 2020; 54: 758-759.

Full Text PubMed - Rowe N and Ilic D. What impact do posters have on academic knowledge transfer? A pilot survey on author attitudes and experiences. BMC Med Educ. 2009; 9: 71.

Full Text PubMed - Ruiz-Barrera MA, Agudelo-Arrieta M, Aponte-Caballero R, Gutierrez-Gomez S, Ruiz-Cardozo MA, Madrinan-Navia H, Vergara-Garcia D, Riveros-Castillo WM and Saavedra JM. Developing a Web-Based Congress: The 2020 International Web-Based Neurosurgery Congress Method. World Neurosurg. 2021; 148: 415-424.

Full Text PubMed - Rush MJ, McPheron A, Martin SJ and Kier KL. Transitioning a regional residency conference from an in-person to a virtual format in response to COVID-19 travel restrictions. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020; 77: 1826-1827.

Full Text PubMed - Sarwal K, Trapido EJ, Sutcliffe S and Qiao YL. Impact and evaluation of International Cancer Control Congresses. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013; 14: 1159-1163.

Full Text PubMed - Schuettfort VM, Schoof J, Rosenbaum CM, Ludwig TA, Vetterlein MW, Leyh-Bannurah SR, Maurer V, Meyer CP, Dahlem R, Fisch M and Reiss CP. Live surgery in reconstructive urology: evaluation of the surgical outcome and educational benefit of the international meeting on reconstructive urology (IMORU). World J Urol. 2019; 37: 2533-2539.

Full Text PubMed - Sloan VS, Grosskleg S, Pohl C, Wells GA and Singh JA. The OMERACT First-time Participant Program: Fresh Eye from the New Guys. J Rheumatol. 2017; 44: 1560-1563.

Full Text PubMed - Steffen J, Grabbert M, Pander T, Gradel M, Köhler LM, Fischer MR, von der Borch P and Dimitriadis K. Finding the right doctoral thesis - an innovative research fair for medical students. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2015; 32: 29.

Full Text PubMed - Stott DB, McMenomy B, Eckmann D, Smith K, Chauhan A, Brady R, Siebert D and Ansel H. Introducing First-Year Radiology Residents to the ACR at the AMCLC From 2009 to 2013: Summary of Experiences and Five-Year First-Cohort Follow-Up. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016; 13: 33-37.

Full Text PubMed - Tamashiro KK, Gomes EK, Beckwith NL, Witten NAK, Morisako A, Leite-Ah Yo K, Carpenter DA and Kamaka M. The Pacific Region Indigenous Doctors Congress Medical Student Track Report. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf. 2019; 78: 45-51.

PubMed - Terhune KP, Choi JN, Green JM, Hildreth AN, Lipman JM, Aarons CB, Heyduk DA, Misra S, Anand RJ, Fise TF, Thorne CB, Edwards GC, Joshi ART, Clark CE, Nfonsam VN, Chahine A, Smink DS, Jarman BT and Harrington DT. Ad astra per aspera (Through Hardships to the Stars): Lessons Learned from the First National Virtual APDS Meeting, 2020. J Surg Educ. 2020; 77: 1465-1472.

Full Text PubMed - Travers R, Wilson M, McKay C, O'Campo P, Meagher A, Hwang SW, Parris UJ and Cowan L. Increasing accessibility for community participants at academic conferences. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2008; 2: 257-264.

Full Text PubMed - Turco MG and Baron RB. Observations on the 2016 World Congress on Continuing Professional Development: Advancing Learning and Care in the Health Professions. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2016; 4-7.

Full Text PubMed - Velasquez SE, Abraham K, Burnett TG, Chapin B, Hendry WJ, Leung S, Madden ME, Rider V, Stanford JA, Ward RE and Chapes SK. The K-INBRE symposium: a 10-institution collaboration to improve undergraduate education. Adv Physiol Educ. 2018; 42: 104-110.

Full Text PubMed - Vita S, Coplin H, Feiereisel KB, Garten S, Mechaber AJ and Estrada C. Decreasing the ceiling effect in assessing meeting quality at an academic professional meeting. Teach Learn Med. 2013; 25: 47-54.

Full Text PubMed - Wang M, Liao B, Jian Z, Jin X, Xiang L, Yuan C, Li H and Wang K. Participation in Virtual Urology Conferences During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-sectional Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2021; 23: 24369.

Full Text PubMed - Wiemken TL, Kelley RR, Pacholski EB, Carrico KW, Peyrani P, Carrico RM and Ramirez JA. The role of infection prevention conferences to build and maintain knowledge-sharing networks: a longitudinal evaluation. Am J Infect Control. 2014; 42: 209-211.

Full Text PubMed - Wilson N, Valencia V and Smith-Bindman R. Virtual meetings: improving impact and accessibility of CME. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014; 11: 231-232.

Full Text PubMed - Wittich CM, Wang AT, Fiala JA, Mauck KF, Mandrekar JN, Ratelle JT and Beckman TJ. Measuring Participants' Attitudes Toward Mobile Device Conference Applications in Continuing Medical Education: Validation of an Instrument. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2016; 36: 69-73.

Full Text PubMed - Woitowich NC, Graff SL, Swaroop M and Jain S. Gender-Specific Conferences and Symposia: A Putative Support Structure for Female Physicians. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020; 29: 1136-1141.

Full Text PubMed - Wren J, Allen K, Proffitt C, Riley H and Aiken M. What is the value and impact of the safety World Conference? Evaluators' reflections of safety 2012. Inj Prev. 2013; 19: 434-435.

Full Text PubMed - Yoon HS, Kwon OS, Lee J, Shin JS, Lee S, Kim SC, Saurat JH, Sterry W and Eun HC. Evaluation of scientific programs at a large-scale academic congress: lessons from the 22nd World Congress of Dermatology. Dermatology. 2012; 224: 38-45.

Full Text PubMed - Zakrzewska JM, Jorns TP and Spatz A. Patient led conferences--who attends, are their expectations met and do they vary in three different countries? Eur J Pain. 2009; 13: 486-491.

Full Text PubMed - Chakhava G and Kandelaki N. Overview of legal aspects of Continuing Medical Education/Continuing Professional Development in Georgia. Journal of European CME. 2013; 2: 19-23.

Full Text - Geissbuhler A, Bagayoko CO and Ly O. The RAFT network: 5 years of distance continuing medical education and tele-consultations over the Internet in French-speaking Africa. Int J Med Inform. 2007; 76: 351-356.

Full Text PubMed - Warden G, Mazmanian P, Leach D. Redesigning continuing education in the health professions. Committee on Planning a Continuing Health Professional Education Institute and Institute of Medicine. 2010:276-97.

- Velin L, Lartigue JW, Johnson SA, Zorigtbaatar A, Kanmounye US, Truche P and Joseph MN. Conference equity in global health: a systematic review of factors impacting LMIC representation at global health conferences. BMJ Glob Health. 2021; 6: .

Full Text PubMed - Gonzales-Zamora JA, Alave J, De Lima-Corvino DF and Fernandez A. Videoconferences of Infectious Diseases: An educational tool that transcends borders. A useful tool also for the current COVID-19 pandemic. Infez Med. 2020; 28: 135-138.

PubMed - Kiwanuka JK, Ttendo SS, Eromo E, Joseph SE, Duan ME, Haastrup AA, Baker K and Firth PG. Synchronous distance anesthesia education by Internet videoconference between Uganda and the United States. J Clin Anesth. 2015; 27: 499-503.

Full Text PubMed - Aithal A, Aithal P. Development and validation of survey questionnaire & experimental data–a systematical review-based statistical approach. International Journal of Management, Technology, and Social Sciences. 2020;5(2):233-51.

- Collingridge DS and Gantt EE. The quality of qualitative research. Am J Med Qual. 2008; 23: 389-395.

Full Text PubMed - Churchill GA. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. Journal of Marketing Research. 1979; 16: 64-73.

Full Text - Hunt SD, Sparkman RD and Wilcox JB. The Pretest in Survey Research: Issues and Preliminary Findings. Journal of Marketing Research. 1982; 19: 269-273.

Full Text - Adomi EE, Alakpodia ON and Akporhonor BA. Conference Attendance by Nigerian Library and Information Professionals. Information Development. 2006; 22: 188-196.

Full Text - Gottlieb M, Sheehy M and Chan T. Number Needed to Meet: Ten Strategies for Improving Resident Networking Opportunities. Ann Emerg Med. 2016; 68: 740-743.

Full Text PubMed - Jimenez-Castellanos A, Ramirez-Robles M, Shousha A, Bagayoko CO, Perrin C, Zolfo M, Cuzin A, Roland A, Aryeetey R and Maojo V. Enhancing research capacity of African institutions through social networking. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013; 192: 1099.

PubMed - Mair J, Lockstone-Binney L and Whitelaw PA. The motives and barriers of association conference attendance: Evidence from an Australasian tourism and hospitality academic conference. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. 2018; 34: 58-65.

Full Text - Knoll MA, Griffith KA, Jones RD and Jagsi R. Association of Gender and Parenthood With Conference Attendance Among Early Career Oncologists. JAMA Oncol. 2019; 5: 1503-1504.

Full Text PubMed - Mehta S, Rose L, Cook D, Herridge M, Owais S and Metaxa V. The Speaker Gender Gap at Critical Care Conferences. Crit Care Med. 2018; 46: 991-996.

Full Text PubMed - Salem V, McDonagh J, Avis E, Eng PC, Smith S and Murphy KG. Scientific medical conferences can be easily modified to improve female inclusion: a prospective study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021; 9: 556-559.

Full Text PubMed - Chu LF, Utengen A, Kadry B, Kucharski SE, Campos H, Crockett J, Dawson N and Clauson KA. "Nothing about us without us"-patient partnership in medical conferences. BMJ. 2016; 354: 3883.

Full Text PubMed - Kish L. HL7 Standards. The blockbuster drug of the century: an engaged patient. 2012. [Internet]. [Cited 23 Oct 2023]; Available from: http://www.hl7standards.com/blog/2012/08/28/drug-of-the-century/.

- Baker A. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington: National Academies Press; 2001.

- Arksey H and O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005; 8: 19-32.

Full Text - Hirt J, Nordhausen T, Appenzeller-Herzog C and Ewald H. Citation tracking for systematic literature searching: A scoping review. Res Synth Methods. 2023; 14: 563-579.

Full Text PubMed - Cooper C, Booth A, Britten N and Garside R. A comparison of results of empirical studies of supplementary search techniques and recommendations in review methodology handbooks: a methodological review. Syst Rev. 2017; 6: 234.

Full Text PubMed - Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC and Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016; 6: 011458.

Full Text PubMed - Harrison R, Jones B, Gardner P and Lawton R. Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS): an appraisal tool for methodological and reporting quality in systematic reviews of mixed- or multi-method studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021; 21: 144.

Full Text PubMed - Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, Gagnon MP, Griffiths F, Nicolau B, O’Cathain A, Rousseau MC, Vedel I and Pluye P. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information. 2018; 34: 285-291.

Full Text - Cook DA and Reed DA. Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale-Education. Acad Med. 2015; 90: 1067-1076.

Full Text PubMed - Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM and de Vet HC. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010; 19: 539-549.

Full Text PubMed