Associations between learning community engagement and burnout, quality of life, and empathy among medical students

Sean Tackett1, Scott Wright1, Jorie Colbert-Getz2 and Robert Shochet1

1Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

2University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA

Submitted: 10/09/2018; Accepted: 17/11/2018; Published: 30/11/2018

Int J Med Educ. 2018; 9:316-322; doi: 10.5116/ijme.5bef.e834

© 2018 Sean Tackett et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use of work provided the original work is properly cited. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0

Abstract

Objectives: To inform evidence-based design and implementation of medical school learning communities (LCs) by investigating which LC components medical students at one school with a multi-component LC were most valued and which were associated with desirable outcomes.

Methods: In this cross-sectional study, all Johns Hopkins School of Medicine (JHSOM) students were surveyed in Spring 2016 regarding perceived value of LC components (peers, faculty advisors, Clinical Foundations of Medicine (CFM) clinical skills course, quarterly reflective discussion sessions, social activities, and LC rooms) with learning environment (LE) perceptions, quality of life, burnout, and empathy assessed as outcomes. Multivariate logistic regressions analyzed associations between LC components and outcomes.

Results: Overall 368/480 (77%) students responded. CFM was highly valued by 286 (80%) students, advisors by 277 (75%). All LC components were significantly associated with favorable overall LE perceptions, but associations with LE subdomains varied. CFM was the only LC component to have significant associations with greater empathic concern (OR 2.1, 95% CI=1.2-3.7) and perspective-taking (OR 1.8, 95% CI=1.0-3.1), less emotional exhaustion (OR 0.4, 95% CI=0.2-0.6) and depersonalization (OR 0.3, 95% CI=0.1-0.5), and good quality of life (OR 3.7, 95% CI=1.9-7.1). Every other LC component, except LC rooms, was associated with greater empathy or enhanced well-being.

Conclusions: Components within an LC are valued differently and vary in their relationships with student outcomes. Future LC research may isolate the effects of and explore interactions among different LC components, leading to more purposeful LC design and allocation of resources.

Introduction

Learning communities (LCs) in undergraduate medical education can be defined as “longitudinal groups that aim to enhance students’ medical school experience and to maximize learning.”1 A growing body of evidence suggests that LCs can benefit medical students in a variety of ways, enhancing their perceptions of the learning environment,2,3 connections with peers and mentors,4,5 satisfaction with advising programs,6–9 performance in clerkships,10 and involvement in leadership and service activities.3 LCs can also benefit faculty participants by improving their clinical skills11 and job satisfaction.12 Perhaps as a result of these benefits, the number of US medical schools with LCs has increased dramatically, from 18 in 2006 to 102 in 2014.13 To date, most studies have treated LCs as single interventions. However, within one institution’s LC program, there is typically a variety of curricular, advising, and extracurricular activities.1,14 Across institutions, there is variation in how LCs are structured, supported, and oriented. For example, in 2012, a study of 66 LCs in the US and Canada found that LCs could have between 1 and 80 different student groups, involve between 1 and 125 faculty, cover 53 different curricular topics, and command a budget ranging from $10,000 to $1,400,000.1 At the heart of LCs are longitudinal relationships among students and between students and faculty, with pedagogic and social learning embedded within LCs in ways that deepen learning and create a sense of wholeness for students.15,16 However, there remains a dearth of understanding about how LCs should be structured to achieve their goals. Because institutions may face different challenges and have different resources to devote to LCs, an understanding of how students value LC components and how they relate to relevant student outcomes could lead to more evidence-based LC design and implementation.

The goal of this study was to determine which LC components were most valued by students and most closely related to measurable outcomes at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine (JHSOM), which has a mature LC that incorporates elements commonly used in medical schools. As LCs appear to be associated with enhanced perceptions of the learning environment2,3 and aspire to enhance student well-being and empathy,8,17 we selected LE perceptions, empathy, quality of life, and burnout as our outcome variables. Because LCs contain curricular, professional, relational, and social aspects, we hypothesized that LC components would be associated with student outcomes in different ways, but that in general, placing a higher value on LC components would be associated with more favorable LE perceptions, greater empathy, and better student well-being.

Methods

Study setting

The JHSOM Colleges Advisory Program is an LC that began in 2005 to enhance students’ clinical skills, professional formation, academic and career advising, and wellness. The LC is organized into 4 “Colleges,” comprising students from all years of medical school. Within each College are smaller groups called “Molecules,” made up of 5 students and their LC faculty advisor. In their Molecules, students engage in the Clinical Foundations of Medicine (CFM) clinical skills course during their first year and have quarterly reflective discussions during all 4 years. The LC also sponsors social activities, and each College is provided a designated space in the medical school building. Table 1 provides additional details of these LC components.

Study design and participants

Data for this cross-sectional study were collected as part of an annual survey, which was distributed electronically to all actively enrolled JHSOM students at the end of the 2015-2016 academic year. We selected to survey all actively enrolled JHSOM students because all would be engaged in the LC at the time of the survey. The study received expedited approval from the JHSOM Institutional Review Board.

Survey composition

Perceived value of LC components

Based on our previous research and experience leading LCs, we developed seven items that were intended to isolate discrete LC components that may already be in place or could be implemented at other institutions. Items asked about the “value to you” for each LC component, with response options along with a five-point Likert scale (1= “No value”, 2= “A little value”, 3= “Some value”, 4= “A lot of value” 5 = “Exceptional value”). The 7 LC components were (1) interacting with peers in Molecules, (2) interacting with peers in Colleges, (3) interacting with faculty advisors, (4) participating in the Clinical Foundations of Medicine (CFM) course, (5) participating in reflective discussion sessions, (6) participating in social activities (e.g. Olympics, happy hours), and (7) having a College room.

Learning environment perceptions

Learning environment (LE) perceptions were measured using the Johns Hopkins Learning Environment Scale (JHLES).18 The JHLES has 28 items, each with five-point response options. During development, exploratory factor analysis resulted in seven domains: (1) Community of Peers, (2) Faculty Relationships, (3) Academic Climate, (4) Meaningful Engagement, (5) Mentorship, (6) Inclusion and Safety and (7) Physical Space. Each item is scored 1-5 so that JHLES totals can range from 28 to 140, with higher scores indicating a more positive LE perception. Validity evidence for content, response process, internal structure and relationship to other variables for the interpretation of scores from the JHLES have been described in previous studies.18–21

Quality of life

Quality of life was assessed using a single-item linear analog self-assessment commonly used in other medical education studies22,23 and in a broad range of other quality of life research.24–26 This item asked individuals to rate their overall quality of life on a 1–5 scale, ranging from “as bad as it can be” to “as good as it can be.”

Burnout

Burnout was assessed using two single-item questions validated in previous studies,27–29 asking respondents to report along with a seven-point Likert scale (1 = daily, 7 = never) how often they felt “burned out from my work” (for emotional exhaustion) or “callous toward people” (for depersonalization).

Empathy

Empathy was assessed using the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI),30 which has been widely used in the general population. The original instrument included four subscales: (perspective-taking, empathic concern, fantasy, and personal distress). We included items for perspective-taking (which measures the cognitive domain of empathy) and empathic concern (which measures the affective domain of empathy). These 2 subscales correlate with the Jefferson Scale of Empathy31 and have been used previously to measure empathy in medical students.32 Each subscale consists of 7 items, scored 1-5 along a Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater empathy.

Data analysis

Basic descriptive statistics were tabulated, with ANOVA and Chi-squared tests for significant differences across class years applied as appropriate.

In bivariate and multivariate analyses, for ease of data interpretation, we dichotomized variables to create odds ratios in logistic regression models. Sensitivity analyses showed that the strengths of associations were not affected when variables were dichotomized compared to if they were treated as ordinal or continuous variables. LC component value was dichotomized by aggregating “exceptional” and “a lot” of value vs. other. JHLES total and domain scores were dichotomized at item means of 3.5, which corresponded to more favorable than unfavorable ratings and approximated the median in most cases. Quality of life was dichotomized as good (aggregating “as good as it can be” and “somewhat good”) or not good. Burnout was dichotomized as high (weekly or more often)27–29 or not high. Empathy was dichotomized at item mean of 4, which approximated the sample median. In logistic regression models, we analyzed the association of highly valuing each LC component with favorable JHLES total and domain ratings. Based on previous work, we hypothesized that effects of LCs on wellness could be mediated through their LE perception.1,20,33 Accordingly, we adjusted for overall JHLES score in multivariate logistic regressions using empathy, burnout, and quality of life as dependent variables. All models adjusted for student gender and year in medical school. Stata 13 was used for all data analyses.

Results

Overall 368/480 (77%) students responded to our survey with response rates across each class exceeding 70%. The average age was 26 years (SD 4.7), and 192 (53%) students were male (Table 2).

Statistically significant differences were found across class years for overall JHLES score (F(3,364) = 7.38, p=0.0001) and its domains of “Community of Peers” (F(3,364) = 5.36, p=0.0013), “Academic Climate” (F(3,364) = 7.97, p=<0.0001), “Meaningful Engagement” (F(3,364) = 12.26, p=<0.0001), and “Mentorship” (F(3,364) = 7.32, p=0.0001). Differences were also seen across classes for emotional exhaustion (χ2(3, N = 368) = 18.7, p<0.001) and quality of life (χ2(3, N = 368) = 11.8, p=0.008). IRI measures of empathy were similar across all class years (Table 2).

Perceived value of LC components

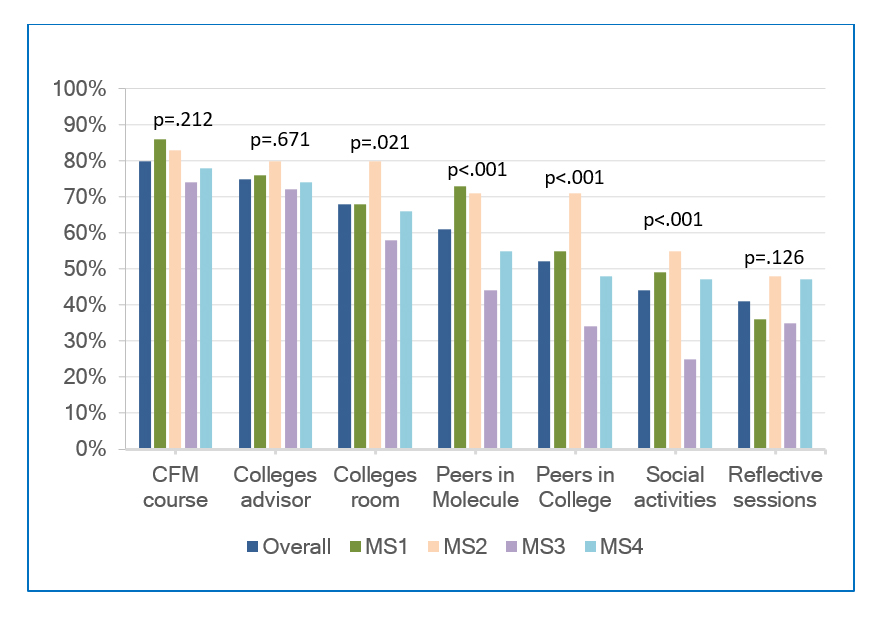

Overall, 286 (80%) students placed high value on participation in the Year 1 CFM course, and this high value assessment was found even among 69 (78%) fourth year students. A total of 277 (75%) placed high value on interacting with their advisors. The strongest differences across classes were found for interacting with peers in Molecules (χ2(3, N = 368) = 22.9, p<0.001), interacting with peers in Colleges (χ2(3, N = 368) = 26.4, p<0.001), and participating in social activities (χ2 (3, N = 368) = 19.1, p<0.001) (Figure 1).

LC components and learning environment (LE) perceptions

All LC components were significantly associated with overall JHLES score and multiple LE domains. After adjusting for gender and class year, the largest magnitudes of associations between LC components and JHLES total were seen with participation in social activities (OR 4.4, 95% CI=2.5-7.8), interacting with advisors (OR 4.1, 95% CI=2.4-6.9), and participation in the CFM course (OR 3.9, 95% CI=2.2-7.0) (Table 3). The CFM course had strongly significant associations (p<.01) with all 7 JHLES domains. The JHLES “Meaningful Engagement” domain was associated with every LC component at p<.01, while the “Mentorship” and “Inclusion and Safety” domains had no statistically significant associations with LC components (other than the CFM course).

LC components and quality of life, empathy, and burnout

After adjusting for effect of overall LE perception, the CFM course was the only LC component to have significant associations with greater empathic concern (OR 2.1, 95% CI=1.2-3.7) and perspective-taking (OR 1.8, 95% CI=1.0-3.1), less emotional exhaustion (OR 0.4, 95% CI=0.2-0.6) and depersonalization (OR 0.3, 95% CI=0.1-0.5), and a good quality of life (OR 3.7, 95% CI=1.9-7.1). Interactions with one’s advisor were significantly associated with empathic concern and less burnout, while reflective sessions were significantly associated with both empathic concern and perspective taking (all p<0.05). Interactions with peers in one’s Molecule and one’s College were significantly associated with quality of life and empathic concern. Valuing the College room was not associated with any of these outcomes (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study of 368 JHSOM medical students, we found variation in how students valued learning community (LC) components and in how valuing LC components related to learning environment (LE) perceptions, quality of life, burnout, and empathy. The Clinical Foundations of Medicine (CFM) course was unique among LC components for being highly valued by large majorities of students across class years and for having positive associations with each outcome we measured.

LCs are meant to enhance students’ learning experiences, which should in turn improve LE perceptions. Rosenbaum described improvements in students’ LE perceptions at the University of Iowa after LC implementation.3 Similarly, Smith found that students at 16 medical schools with LCs had more positive perceptions of the pre-clerkship LE as compared to students at 8 schools without a LC, with significant differences for nearly every item on the Medical School Learning Environment Survey.2 In our study, all components of the JHSOM LC were related to positive overall LE perceptions, with specific LE domains from JHLES having different relationships with each LC component. In particular, we found that “Meaningful Engagement”, which relates to a student’s sense that he or she is valued by the medical school, was linked with all 7 LC components we studied. This could indicate that LCs that employ different combinations of LC components may improve student affiliation with their institution, something that has been receiving greater attention within the academic community.34,35 Conversely, the LE domains of “Inclusion and Safety”, which refers to students’ perceptions of discrimination and mistreatment, and “Mentorship”, pertaining to students’ perceptions of identifying clinical and research mentors other than their assigned LC advisors, were not closely related to LC components and therefore may not be as responsive to LC-based interventions.

Just as there were distinctive patterns in how LC components related to LE perceptions, there were variations in how they related to students’ empathy and well-being. Valuing reflective sessions had a strong association with a single outcome, empathy, but no association with burnout or quality of life. We cannot determine causation, but it is possible that these sessions - which were intended to provide students the opportunity to process their feelings on difficult encounters with a group of trusted individuals and thereby enhance empathy - may have had their intended effect. Interactions with peers and advisors exhibited a second distinct pattern of relationships with outcomes, showing positive associations with more than one type, as each was associated with affective empathy and aspects of well-being. This is consistent with previous work20,36–38 and suggests that structures that foster relationships may have broader impacts than others. The Colleges rooms, which give groups of students specific places to congregate, was associated with yet another pattern, not having associations with any of the outcomes, despite being highly valued by over two-thirds of students. While the physical environment and actual spaces are believed to influence learning and morale in medical education,39 how one creates settings that facilitate the enhancement of medical student connectedness and fulfillment is poorly understood. This may deserve further investigation considering the finances associated with building and renovations.

The CFM course was unique among LC components for being highly valued across all class years and having strong associations with favorable LE perceptions, greater empathy, and better well-being. Clinical skills courses are common components of medical school LCs,1 and studies have consistently shown that early clinical experiences by medical students can have a variety of benefits, including fostering clinical skills, stimulating professional development, sparking motivation, and bolstering confidence.40,41 Early clinical skills courses embedded within LC structures have likewise been associated with improved clinical evaluations.10,42 To our knowledge, ours is the first study to show associations between an LC clinical skills course and greater learner empathy and well-being. Additionally, although the CFM course was conducted within peer Molecules and taught by the LC advisor, CFM was valued more highly and was more strongly associated with favorable outcomes than either of these individual LC components. Likewise, while the timing of the course, as medical students are beginning their professional development in a new academic environment, could be significant, students are also engaged in sponsored social activities then, which we found to have few relationships with empathy and well-being. Our suspicion, which would need confirmation in future study, is that the unique structure and process of LC learning – small groups of students connected to a teacher who knows them beyond the boundaries of the classroom, journeying together over time, and learning with and from peers in this context – creates a “safe space” for learning and reflection that is greater than the sum of its parts, and may have an enduring impact on students’ professional development. 43 - 45

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, we can only describe associations among variables in a cross-sectional study; a longitudinal study may be able to demonstrate whether LC components cause improvements in student well-being and empathy. Second, although JHSOM’s LC model of curricular and advising components are shared by other medical school LCs,46a multi-institutional study would be needed to demonstrate whether our findings would be comparable at other schools with similar or different LC structures. Third, we used the students’ perceived value of the components of the LC as a marker for their engagement with each component based on their responses to items newly created for this study. While our process for creating the items generated content validity evidence and items’ use in this study generated relations to other variables evidence, future work would be needed to validate these items better. Finally, our surveys relied on student self-report which could be prone to bias. Other measures, such as more objective measures of academic achievement related to CFM course competencies or a qualitative analysis of the LC experience would add to our understanding of the value of learning in an LC context.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study showed that LC components are valued differently by students and likely impact students in variable ways, suggesting that future LC research should seek to disentangle the effects that each LC component has. By describing the associations LC components have with desirable student outcomes, we contribute evidence that could lead to more efficient resource allocation for those seeking to develop or refine their own LCs. A significant finding in this study was the importance of the first-year LC clinical skills course, which suggests that LC educational structures interweaving curricular learning of clinical content, advising, and longitudinal peer and faculty relationships may be particularly beneficial. We hope that this work can pave the way for future studies to understand better the role that LCs can play in medical students’ well-being, skill development, and professional formation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Smith S, Shochet R, Keeley M, Fleming A and Moynahan K. The growth of learning communities in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2014; 89: 928-933.

Full Text PubMed - Smith SD, Dunham L, Dekhtyar M, Dinh A, Lanken PN, Moynahan KF, et al. Medical student perceptions of the learning environment: learning communities are associated with a more positive learning environment in a multi-institutional medical school study. Acad Med. 2016;91(9):1263-9.

- Rosenbaum ME, Schwabbauer M, Kreiter C and Ferguson KJ. Medical students' perceptions of emerging learning communities at one medical school. Acad Med. 2007; 82: 508-515.

Full Text PubMed - Bicket M, Misra S, Wright SM and Shochet R. Medical student engagement and leadership within a new learning community. BMC Med Educ. 2010; 10: 20.

Full Text PubMed - Brandl K, Schneid SD, Smith S, Winegarden B, Mandel J and Kelly CJ. Small group activities within academic communities improve the connectedness of students and faculty. Med Teach. 2017; 39: 813-819.

Full Text - Coates WC, Crooks K, Slavin SJ, Guiton G and Wilkerson L. Medical school curricular reform: fourth-year colleges improve access to career mentoring and overall satisfaction. Acad Med. 2008; 83: 754-760.

Full Text PubMed - Levine RB, Shochet RB, Cayea D, Ashar BH, Stewart RW, Wright SM. Measuring medical students' sense of community and satisfaction with a structured advising program. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:125-32. DOI: 10.5116/ijme.4ea7.e854

- Fleming A, Cutrer W, Moutsios S, Heavrin B, Pilla M, Eichbaum Q and Rodgers S. Building learning communities: evolution of the colleges at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2013; 88: 1246-1251.

Full Text PubMed - Sastre EA, Burke EE, Silverstein E, Kupperman A, Rymer JA, Davidson MA, Rodgers SM and Fleming AE. Improvements in medical school wellness and career counseling: A comparison of one-on-one advising to an Advisory College Program. Med Teach. 2010; 32: e429-e435.

Full Text - Jackson MB, Keen M, Wenrich MD, Schaad DC, Robins L and Goldstein EA. Impact of a pre-clinical clinical skills curriculum on student performance in third-year clerkships. J Gen Intern Med. 2009; 24: 929-933.

Full Text PubMed - Wenrich MD, Jackson MB, Ajam KS, Wolfhagen IH, Ramsey PG and Scherpbier AJ. Teachers as learners: the effect of bedside teaching on the clinical skills of clinician-teachers. Acad Med. 2011; 86: 846-852.

Full Text PubMed - Wagner JM, Fleming AE, Moynahan KF, Keeley MG, Bernstein IH and Shochet RB. Benefits to faculty involved in medical school learning communities. Med Teach. 2015; 37: 476-481.

Full Text - LCME. NNumber of Medical Schools Organizing Students into Colleges or Mentorship Groups. [Cited 10 Nov 2017]; Available from: https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/cir/425510/19a.html.

- LCME. Curriculum Inventory and Reports (CIR) - Initiatives - AAMC. [Cited 10 Nov 2017]; Available from: https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/cir/425104/19d.html.

- Shapiro NS, Levine JH. Creating Learning Communities: a practical guide to winning support, organizing for change, and implementing programs. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc; 1999.

- Boyer EL. Campus life: In search of community. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ; 1990.

- Osterberg LG, Goldstein E, Hatem DS, Moynahan K and Shochet R. Back to the future: what learning communities offer to medical education. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development. 2016; 3: JMECD.S39420.

Full Text - Shochet RB, Colbert-Getz JM and Wright SM. The Johns Hopkins learning environment scale: measuring medical students' perceptions of the processes supporting professional formation. Acad Med. 2015; 90: 810-818.

Full Text PubMed - Tackett S, Bakar HA, Shilkofski NA, Coady N, Rampal K and Wright S. Profiling medical school learning environments in Malaysia: a validation study of the Johns Hopkins Learning Environment Scale. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015; 12: 39.

Full Text PubMed - Tackett S, Wright S, Lubin R, Li J and Pan H. International study of medical school learning environments and their relationship with student well-being and empathy. Med Educ. 2017; 51: 280-289.

Full Text PubMed - Colbert-Getz JM, Tackett S, Wright SM and Shochet RS. Does academic performance or personal growth share a stronger association with learning environment perception? Int J Med Educ. 2016; 7: 274-278.

Full Text PubMed - West CP, Shanafelt TD and Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011; 306: 952-960.

Full Text PubMed - West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA and Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA. 2009; 302: 1294-1300.

Full Text PubMed - Spitzer WO, Dobson AJ, Hall J, Chesterman E, Levi J, Shepherd R, Battista RN and Catchlove BR. Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: a concise QL-index for use by physicians. J Chronic Dis. 1981; 34: 585-597.

PubMed - Rummans TA, Clark MM, Sloan JA, Frost MH, Bostwick JM, Atherton PJ, Johnson ME, Gamble G, Richardson J, Brown P, Martensen J, Miller J, Piderman K, Huschka M, Girardi J and Hanson J. Impacting quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24: 635-642.

Full Text - Gudex C, Dolan P, Kind P and Williams A. Health state valuations from the general public using the visual analogue scale. Qual Life Res. 1996; 5: 521-531.

PubMed - West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sloan JA and Shanafelt TD. Single item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are useful for assessing burnout in medical professionals. J Gen Intern Med. 2009; 24: 1318-1321.

Full Text PubMed - West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV, Sloan JA and Shanafelt TD. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2012; 27: 1445-1452.

Full Text PubMed - Cook AF, Arora VM, Rasinski KA, Curlin FA and Yoon JD. The prevalence of medical student mistreatment and its association with burnout. Acad Med. 2014; 89: 749-754.

Full Text PubMed - Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;44(1):113-26.

- Hojat M, Mangione S, Kane GC and Gonnella JS. Relationships between scores of the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSPE) and the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). Medical Teacher. 2009; 27: 625-628.

Full Text - Berg K, Blatt B, Lopreiato J, Jung J, Schaeffer A, Heil D, Owens T, Carter-Nolan PL, Berg D, Veloski J, Darby E and Hojat M. Standardized patient assessment of medical student empathy: ethnicity and gender effects in a multi-institutional study. Acad Med. 2015; 90: 105-111.

Full Text PubMed - Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, Fischer MR, Wirtz M, Woopen C, Haramati A and Scheffer C. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011; 86: 996-991009.

Full Text PubMed - Yengo-Kahn AM, Baker CE and Lomis AK. Medical students' perspectives on implementing curriculum change at one institution. Acad Med. 2017; 92: 455-461.

Full Text PubMed - Sklar DP. What can we learn from the letters of students and residents about improving the medical curriculum? Acad Med. 2017; 92: 421-423.

Full Text PubMed - Maslach C, Schaufeli WB and Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001; 52: 397-422.

Full Text - Dyrbye LN, Power DV, Massie FS, Eacker A, Harper W, Thomas MR, Szydlo DW, Sloan JA and Shanafelt TD. Factors associated with resilience to and recovery from burnout: a prospective, multi-institutional study of US medical students. Med Educ. 2010; 44: 1016-1026.

Full Text PubMed - Tempski P, Santos IS, Mayer FB, Enns SC, Perotta B, Paro HB, Gannam S, Peleias M, Garcia VL, Baldassin S, Guimaraes KB, Silva NR, da Cruz EM, Tofoli LF, Silveira PS and Martins MA. Relationship among Medical Student Resilience, Educational Environment and Quality of Life. PLoS ONE. 2015; 10: 0131535.

Full Text PubMed - Nordquist J. Alignment achieved? The learning landscape and curricula in health profession education. Med Educ. 2016; 50: 61-68.

Full Text PubMed - Dornan T, Littlewood S, Margolis SA, Scherpbier A, Spencer J and Ypinazar V. How can experience in clinical and community settings contribute to early medical education? A BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2009; 28: 3-18.

Full Text - Yardley S, Littlewood S, Margolis SA, Scherpbier A, Spencer J, Ypinazar V and Dornan T. What has changed in the evidence for early experience? Update of a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2010; 32: 740-746.

Full Text - Osterberg L, Gilbert J, Lotan R. From high school to medical school: the Importance of community in education. Medical Science Educator. 2014;24(3):353-356. DOI: 10.1007/s40670-014-0060-z

- Chou CL, Johnston CB, Singh B, Garber JD, Kaplan E, Lee K and Teherani A. A "safe space" for learning and reflection: one school's design for continuity with a peer group across clinical clerkships. Acad Med. 2011; 86: 1560-1565.

Full Text PubMed - Hauer KE, O'Brien BC, Hansen LA, Hirsh D, Ma IH, Ogur B, Poncelet AN, Alexander EK and Teherani A. More is better: students describe successful and unsuccessful experiences with teachers differently in brief and longitudinal relationships. Acad Med. 2012; 87: 1389-1396.

Full Text PubMed - Haidet P and Stein HF. The role of the student-teacher relationship in the formation of physicians. The hidden curriculum as process. J Gen Intern Med. 2006; 16-20.

Full Text PubMed - Goldstein EA, Maclaren CF, Smith S, Mengert TJ, Maestas RR, Foy HM, Wenrich MD and Ramsey PG. Promoting fundamental clinical skills: a competency-based college approach at the University of Washington. Acad Med. 2005; 80: 423-433.

PubMed